“After getting too know lots of doubles, I’ve come to feel that the future is theirs. They have the most to teach us about crossing cultural boundaries, something which more and more of us will have to do in the years ahead.”

[S]hortly after filmmaker Regge Life arrived in Japan in 1990, a Japanese movie crew member eagerly asked to see his gun. “I was African-American and from New York,” Life recalls, “so even this educated man assumed I’d be packing a pistol. He’d learned that from the media.” Not an auspicious beginning for what was soon to evolve into a bi-national media effort aimed at dissolving stereotypes.

Regge Life and his Global Film Network have now completed a documentary trilogy which candidly explores the personal, intimate side of the Japan-America relationship. Starting with Struggle and Success: The African-American Experience in Japan, then Doubles: Japan and America’s Intercultural Children, and finally After America . . . After Japan, his new film about the trials and joys of returnees, Regge Life has illuminated the increasingly blurred boundaries of race, culture and identity.

Life’s moving documentaries, broadcast nationally in both countries, introduce us to scores of reflective people who in turn invite us to take a closer look at ourselves. Transcending Japan or America, these films concern themselves with what it means to build a human identity out of disparate parts. While making his programs, Life readily allows, he has himself been remade through exposure to Japanese values and ways.

Life’s deep-seated itch to explore the frontiers of culture was implanted during his “inter-everything” upbringing as the son of middle-class parents in Westchester County, New York. Attending progressive, integrated schools where he made friends with Jews, fellow blacks, blue collar Italians and other ethnic Americans, Life grew steadily more curious about his own elusive identity as an African-American. Nearing the end of his undergraduate years in 1971, while studying towards a double BA in drama and sociology at Tufts, Life joined an overseas program that took him to Ibadan, Nigeria for a year of coursework in theater arts. Having just settled a bitter civil war, the country’s infrastructure lay in ruins. Once Life got over the culture shock, he grew close to his Nigerian classmates, trading off piece by piece all of his Western clothes for their hand-woven African garments.

After Nigeria, Life traveled slowly up the coast of West Africa and northward into Europe. “It wasn’t until I left Morocco and got to Spain,” he says, “that I went into a store to buy a shirt and some pants. Even the Africans weren’t walking around Madrid in African robes.” In England, down to the last of his money, Life boarded a plane bound for New York. The islands of Japan, “which would bring it all into focus,” were still well beyond the horizon, as was his groundbreaking career in film and TV. For now, it was simply time to go home and discover, as do the souls we meet in his newest film, that life back there would never be the same.

Stewart Wachs: What was your first “return” experience like for you?

Regge Life: My old friends had a welcome home party the night I arrived back in New York. And I remember I had on these four-inch platform shoes made of lizard skin by a shoemaker in London called Jumpin’ Jack Flash, and huge bellbottoms that were trendy in England at that time. I was Mr. London, comin’ back. And I walked straight into another cultural world. So I felt strange, out-of-place. And this continued for awhile.

My room in the family house had been taken over by my brother. I was now living in the basement. And I remember staying down there a solid three weeks, not going out much, answering few phone calls, because I was still trying to process where I was. What did I just come from, and what were people here doing now? What was everybody thinking? And me now having this worldview.

I realized that despite all the TV and newspapers we had, most Americans didn’t have a worldview. And that’s what was banging on my mind when I did go out, to hear people say things I knew were completely false. And then trying to give them some other information based on where I had been, saying, “No, no, I’ve been to that place, and that’s incorrect.” But people believe this stuff because that’s all they’re getting. No one’s investing in a subscription to a newspaper or magazine published outside of the U.S. to get another viewpoint. They just believe what’s coming over the evening news. And this was back when the evening news at least had some integrity.

Had the idea of doing something professionally about such stereotypes and misinformation arisen in your mind?

No, not at all. I was essentially trying to come back and find a job like everybody else. One day the phone rang and someone said, “I am the stage manager for the national touring company of The River Niger. I need an assistant stage manager. Can you fill it?” “Yeah!” So we went into rehearsal for two weeks, and for the next nine months I was on the road with a Broadway show. It was a true rite of passage. Here was the real world of entertainment, this cachet, from city to city, of being the hottest ticket in town, and feted and partied . . .

What a world to step into, not just out of college, but fresh out of West Africa . . .

Yeah, it was a fine company, and I made friends. Still, by that ninth month I was a little weary. I had been in Nigeria for a year, and now on the road for almost another year. You just start to feel rootless. And you realize that you’re in this world of people who do this all their lives. Most of the folks in this company never really performed in New York anymore. They were always on the road, and used to it. But I said, “I don’t think this is what I want to do.” So I jumped ship in Chicago and finally made my way back to New York. I had decided to study directing.

This is when the film thing hit. I got into New York University Film School and did the two-year MFA program. I came out and slowly started this process of independent work, documentaries. I went back to West Africa. I did a couple of ethnographic documentaries in Nigeria. Then some work in the Caribbean. These were well-received. It was then that this sense of the other, of cultural awareness, of trying to bring another worldview to American audiences really began, with real tools now, because I had this camera and the ability to tell a story visually.

At what point did you become interested in Japan?

That happened in my first year of film school. An old high school friend, Alison, a pianist, had just come back to New York from more than three years in Kyoto. She called and said, “Regge, I want you to come over. I have something to share with you.” When I visited her that night, she opened the door and here she was dressed in full kimono, and the whole ambience of her apartment was totally Japanese. And she had, during those three years, learned how to play the koto. From piano to koto. So that evening I was entertained with a concert. She told stories and showed pictures, and I was enchanted. “Wow,” I said, “you made it, you did it.” And she said, “Regge, you should get there one day. It’s really an interesting place.”

I had seen a few Japanese movies, but after that I got really crazy about them and went to these Japanese film festivals and Kurosawa retrospectives at The Elgin in New York, and got exposed to Naruse Mikio and Kinoshita Keisuke and directors I didn’t even know about. So I’d cut school and see movie after movie. I saw films like The Ballad of Narayama and Banished Orin, which were so beautifully photographed and put this whole idea into my head of non-linear, non-verbal storytelling.

Many years passed while I did other work, documentaries, feature films like Ragtime and Trading Places, and TV, but I was still watching Japanese movies. And like most New Yorkers I’d go to a sushi restaurant once in a while. No big Japanophile kind of life. But then a musician friend, Rene McClean, came back from a year in Japan on a project through the National Endowment for the Arts. And he was high on Japan. Of course, this was 1988, the height of the Japan bubble. And Rene said, “Hey man, you gotta get there. It’s poppin’!” Now, Rene was somebody like myself who was working outside America, who had this other viewpoint.

He told me to apply for the NEA Japan program, that I’d thank myself later. He said, “There’s very few African-Americans that go. They’ll be excited just to see your application.” So I wrote the required essay about why I’d want to spend six months in Japan. And my theme was, quite honestly, that I’d been enamored of Japanese movies and thought it would be a great contribution to my work to experience this style of filmmaking firsthand.

I applied for ‘89, but ‘90 is when I went. While preparing to go and trying to find out what was happening in the Japanese film scene, I got my first wake-up call; the disappointment of finding out that all that prolific filmmaking I was in love with wasn’t happening anymore. That TV and the bubble economy had really hurt the Japanese film industry. All of these famous directors couldn’t get deals.

During a boom economy? Why not?

Well, most of the films they wanted to make were not exportable. And even for the domestic audience, Japanese distributors would rather buy a European or American blockbuster than their own movies. Meanwhile, the studios were selling off their movie lots to department store chains like Mitsukoshi, because all of that land in Tokyo and the suburbs was now worth a fortune. The tsubo had gone up ten times. The bottom line was, Regge, the world you’ve been observing and in love with doesn’t exist anymore.

I had come to know Ozu Yasujiro’s work on video and the films of many other directors at Japan Society screenings, and was knocked out by it. And in the process of loving Ozu, of course, you fall in love with Hara Setsuko. She’s so beautiful, and her whole style exemplifies the Western concept of the Japanese woman. Not geisha per se, but this vulnerability, softness, femininity, a warmth that just beckons you, that says please come to Japan! I remember people telling me Hara Setsuko is the Greta Garbo of Japan. She’s close to 80 years old but no one sees her anymore. We don’t even know if she’s alive or dead. So she became for me almost a metaphor for the Japanese movie industry. But I was undaunted. There had to be somebody making movies.

And then as fate would have it — and I believe the Lord works in mysterious ways — I was due to go in April of 1990, and a week after my birthday in January I had a horrible skiing accident. I ended up in the hospital with a nine-month rehabilitation because they had to rebuild my entire left knee.

I watched nine more months of Japanese movies. I went through the entire collection at Tokyo Video in New York, and most of what was in the Japan and Asia Societies. In the process I met Somi Roy, from Singapore I think, who had just had this festival of independent Japanese film directors, kind of young Turks. And one he had become very close with was Ando Kohei, who did very surrealistic films but was approachable. So I wrote Ando, and he sent me paperwork on this feature film director named Yamada Yoji, who I had never heard of.

But who is a household name in Japan…

Right, but almost no one in America knew him. And I asked some of the people Stateside who were helping me, and they said oh yeah, well that’s that Tora-san movie, that’s not what you want to do. But from what Ando Kohei had said, here was a guy who was making movies.

About forty-two by that point…

Right. So I wrote a letter, and through a series of introductions I eventually came to be accepted by Yamada Yoji’s group. I didn’t even know at the time how groundbreaking that was. I found out later that no one else had ever been given that honor. Again, most foreigners and Japanese are not bilingual, and there’s a real fear of the non-speaker on the set. And also that whole world of Tora-san was a closed world; it really was this family. I’ve learned over the years that trying to get into family in Japan is the biggest obstacle that any non-Japanese faces. And family is sometimes more the company than the family you go home to.

So now I had a place to go, a willing filmmaker, and it was just about setting a date. So I’m hassling with the doctors: can I leave at this point? But they wanted me to do nine months to the day. So I set my date in October. And this is when I got my first experience with, not just punctuality, but that when you say something in Japan you’ve got to follow it up. Because no one makes you sign on a dotted line, or calls you again.

Now, I don’t know what date I gave these guys, but on that date and time I was still home in New York packing. And the phone rings. On the other end is Ando Kohei, calling from Tokyo: “Where are you?” he says. “Well, obviously I’m in New York.” “You’re supposed to be here! We’re all sitting at dinner, waiting to welcome you. Don’t you remember you gave us this date?” And I’m in New York packing! And so you also learn about the wonderful world of apology. I was apologizing profusely. “Well,” Ando says, “please don’t do this again. Mr. Yamada’s here, people from the Shochiku Company are here. This means a lot.”

I finally got there a week late. And getting there was elaborate. I flew to Los Angeles and then took a day off to let the knee not lock. And then to Hawaii and another one-day layover for the knee, and then finally to Japan. And because of my condition I had a friend in New York have another friend in Tokyo meet me at the airport, who got me onto the train to Ueno, and then by subway to Roppongi. I had a cane at this point. I’m staggering through Ueno with a couple of bags and a cane and sensory overload: “Where am I? What’s going on here?” And it’s a good thing this woman was with me, kind of just tugging me along, “This way, this way.” Had I arrived by myself I’d have gotten lost en route. But it all started from there.

Recently I went out with friends to find the original restaurant I went to my first night in Tokyo, a little, home-style Japanese restaurant, kinda smoky and greasy. I remember eating Japanese food there I had never eaten in America, and thinking, it’s been a little crazy, and I’ve been through an ordeal to get here, but it’s really gonna be all right. The biggest thing right then was where I was going to live, and adjusting to this whole sense of space in Japan. But once I’d made that leap of faith, Mr. Yamada set me up with homestays.

So you were not only working with Japanese, but living with them.

Yes, it was a total immersion. Every night I’d go home, just like the typical Japanese salaryman, on the monorail from Ofuna to Kataseyama, which is a fairly affluent community in the Tokyo area. But the people who I was living with, the Sasayas, were not affluent people. The wife spoke English, but the husband didn’t. They were gracious, and they really — and I’m sure this was Mr. Yamada’s insistence, too — they really made sure I knew what living as a Japanese was. Mr. Yamada was like Ozu in this way. When Ozu filmed, he insisted everything on the set be real. So when he did scenes of men drinking sake, they really drank sake. And as you know, the filmmaking process is take after take after take. So when you get to the ends of some of those scenes I guess the actors were pretty crocked.

This is what Mr. Yamada wanted me to experience. Not this kind of part-time Japan experience. In other words, when you leave the studio, you don’t go off to some gaijin ghetto and speak English and eat hamburgers and come back to hang out with Japanese like you’re going to Disneyland. No, you get on the crowded train, walk the ten minutes through the jammed station, come back and say “tadaima” to your host family, then you eat your dinner, wait for your turn in the bath, watch television with them, maybe sip a beer with the father and try to communicate in rudimentary Japanese or sign language. But you try, and then you retire to your little three-and-a-half mat space in their home. And there you go.

How long did you stay with the Sasayas?

The first two and a half months, almost half of my stay. And then I moved to another family, again friends of Mr. Yamada. This family was fairly affluent. They owned clothing businesses and lots of other stuff. So here was the other side of Japan, that Omotesando, Oyama-dori side, of beautiful clothes and leisure lifestyle and golfing, the image most Americans then had of the rich Japanese. But their money was not new. They had lived well for centuries, I’m sure. So my second stay was like 180 degrees the other way.

Let’s turn to the professional side of it, your work with Yamada Yoji. What did you learn, and how did you go about learning it with such limited Japanese?

I had brought with me a Hi-8 camera. I’d gotten permission to shoot while we were making the Tora-san movie, because I figured all of this would happen so fast I’d probably want to have a second look. It was just a matter of photographing stuff I wanted to use as a reference later, a documentation of this whole experience, and of interacting with them on a real human level, not as any kind of vaunted observer on the set. Drinking tea during breaks with the actors, hanging out with the crew at night when they would go and have soba, yakitori, hundred-yen sushi, whatever. Just being down-to-earth and ordinary, trying as much as possible to shed this foreigner special treatment. And many times they still did stuff for you ‘cause you are the guest. But I tried to lose as much of that as I could. I realized that the charm of the Tora-san films, of that whole film crew, was this effort to make it authentic. It was not this heightened, larger-than-life thing. It was real life in shitamachi, in the community. And I realized that in American filmmaking we really don’t have anything like this. No one tries to make it feel real. We want to make it heightened, and in some ways caricatured. Here was an attempt to capture life as it really happened, and to celebrate the joy of just being Japanese — the food, the interactions, how people worked out everyday life problems.

Do you think that maybe the fact that you ended up with a director of features working at almost a documentary level influenced you to come back to documentaries?

Not really. When I was with Mr. Yamada I was still thinking only of feature films, story-driven movies. The documentary thing came after the whole experience and I was about to leave Japan. I’d had a good time, and had this feeling that six months wasn’t enough. But if you’re going to come back here, what are you going to do? And I was not in that head, like a lot of people, who are going to just teach English, or just want to be here. I wanted to make a contribution based on what I did in my life. While I had been observing Mr. Yamada, I had been learning some important lessons out on my own. I was meeting lots of African-Americans, for instance, who had decided to make Japan their home, in places where I’d never expected to find them. And a surprising number seemed happy with their lives.

I’d heard plenty about discrimination against people of color in Japan. I knew very well that some politicians had made disparaging remarks. So I expected, and found, some prejudice. But I also discovered a lot of African-Americans happy in a variety of professions—commerce, fashion design, journalism, education, not only the more stereotypical fields like sports or entertainment. And a number of them told me that they found living in Japan more comfortable and satisfying than living in the U.S. Whenever they did face discrimination in Japan, it was usually not because they were black, but because they were foreigners. This was something they could share with all of the other gaijin here. They were not alone. One after another, they told me that for the first time in their lives they were being judged by their ability and performance, and not by the color of their skin.

Meeting people like John Russell, JR Dash and others all around Japan, that’s what kicked off the idea for Struggle and Success. And I realized it would be a lot easier to do as a documentary than to sit down with pen and paper and try to create a story with these people, some kind of theatricalized thing. I said let me just go with the real, and that’s what I did.

Soon after your six months with Yamada Yoji you were back in Japan, funded and into production on Struggle and Success. How did you get the project on its feet so quickly?

Well again, we’re talking about bubble-era Japan, and the creation of a new funding entity called The Center for Global Partnership, or CGP. And luckily for me, as my six months was ending, CGP was being born. At my departure briefing with my sponsors I learned about it, and that if I wanted to do something now was the time, ‘cause they were just unpacking the boxes. The man in charge of CGP had been in the Japan Foundation bureaucracy for a long time, but was not a bureaucratic guy. He saw CGP as this final opportunity to do something different. And luckily for me, he was young and energetic. Even the staffing was not all from Tokyo or even Japanese. There were Americans who could speak Japanese.

So now you had the money, the idea, some people to interview — How did you put together a crew, and moreover a Japanese crew?

Well again, lucky for me, Megumi, the woman who had met me when I first arrived in Japan, worked in the film business. So I called upon her expertise to help me find shooters. Because the one thing I had made a decision about was I was not bringing Americans to Japan to do this documentary.

Why not?

Because I knew Americans would not understand the sensibility I wanted to bring to the work, which was clearly what I had learned from Mr. Yamada. And I knew no American cinematographer — I shouldn’t say that; none that I was aware of — would probably understand what I wanted to do. I said look, if I’m going to do a film in Japan, I’m gonna work locally, so please help me find a crew. Megumi was really efficient, so we got lots of introductions. I kept meeting different film crews and cinematographers, many of whom made me realize how blessed I had been to work with Mr. Yamada, because these guys chain-smoked or couldn’t really speak any English, and didn’t seem to have any interest in trying to communicate with me. It was almost a take it or leave it attitude if you were going to use them. So I kept looking and getting introductions, and was starting to get a little nervous because I was thinking, “Oh my gosh, is there nobody out here?” Then I found a fixer, a person who fixes crews for foreigners shooting in Japan. And through her I finally got to somebody who had worked with another American producer, but there was this sense that this guy wanted, for lack of a better word, to comment on what I wanted to do. In other words, “Yeah, I’ll shoot this film for you, but I have to add my comment.”

How did he communicate that to you?

Through Megumi, he just said, “We can do this, but because you don’t understand Japan . . .” You know.

They didn’t trust your knowledge of Japan, your sensitivity to it?

Right, and their sense was, and I find this in the documentary tradition in Japan, not just them, that certain people in the chain have this ability to kind of step outside of the program. Many narrators that do Japanese documentaries add their comments to the track. They don’t just read it, they have this kind of license. I said, “Well I don’t know if I can go with that,” so we just kept looking. Finally, I was at my wit’s end and ready to give up and say I guess I have to find some American guys and bring ‘em over here and feed ‘em, clothe ‘em, and hear ‘em whine about the lack of hamburgers or something. And then we took a second look at a brochure from a company I thought only rented equipment. Megumi called them and they told her, “We rent but we also shoot.” So we went over. And I think the giveaway that these guys were the ones was their response when I asked them, “Can I see a reel?” Most of the time you’d get this bristled response, like, what do you mean you want to see my work? I’m introduced by so-and-so, so you hire me. Again, that’s the Japanese system. But I said no, I’m an American, and yes, since I’m going to work closely with you I’ve got to know how you work. Well, these guys had no problem with that. They said, “Oh sure, whaddya wanna look at? Temples? People?” They started putting in tapes, and I was back in that world of Japanese films, ‘cause everything they were showing me was beautiful images and composition, just what I wanted. I met the older cameraman who had done all the work, Shimazu Hisazumi, and found out he had been to thirty-something countries. Then I knew that my search had ended. I’d found a Japanese who was open to working with a foreigner.

Of course at first, they didn’t know exactly what I wanted. They were used to shooting documentaries in Japan, which are shot with a certain kind of coverage. So the first day they did what I wanted to do and then they did what they had been doing, just to give me stuff. I found it a little humorous, but we’re working on a relationship here, so I said it’s no big deal, we’ll get it together. And we kept shooting and shooting.

Then finally, I think we were in Kobe, and Megumi had wanted to remain in Tokyo, so I had to get an interpreter. I soon found out that this interpreter wasn’t really doing right by me. I would be directing the crew and then she would add her comment to what I was saying and many times obstruct it. Because in her mind it was, “Oh, I think he should shoot it this way.”

How did you find this out?

Luckily it was the sound man who, in that wonderful way in Japan when somebody says “I speak no English” but that doesn’t mean they don’t understand English. He understood everything I was saying. Apparently one night he called a little meeting and said, “We’re not shooting the movie Mr. Life wants shot. She’s not giving us the right instructions.” By then they were into the spirit of what I was doing and were behind me. So they said to me, “We want you to make a good film, but to do that, you must get rid of her.” We were to meet in Shinjuku for a day of shooting, and they said, “We’ll come thirty minutes late today. When she comes on time, fire her. Don’t worry, we don’t need an interpreter, we’ll be fine.” So she showed up, and I said, “Listen, it’s not working, I’m sorry.” Then the crew showed up with a total change in attitude. Laughter, smiles, this burden had been lifted. And for the rest of the shoot we just kicked butt. Ultimately the crew all came to the premiere in Tokyo at the American Club. They put on their suits and ties and just sat there, puffed up. And I introduced them and they were just as reserved and shy as Japanese can be. But they were so proud to stand up and be applauded by these two hundred Americans for the work they had done. It started a tone between us and I recently had a chance, on our third film, to bring them to New York, to actually take them to my home. They met my dad, my daughter, my dog. And for me that was the full circle, because it was like what Mr. Yamada had done for me. He didn’t just say, “Come watch us shoot.” I got to see the real life.

In addition to interviewing 70 people for Struggle and Success you researched the history of relations between African-Americans and Japanese from the Meiji period onwards. Did you learn anything important that you couldn’t fit into the documentary?

Yes. There’s a whole legacy, particularly during the 1930s and ‘40s in America. I don’t want to misquote, so I would urge people to pick up a new book entitled African-American Views of the Japanese by Reginald Kearney. His book is quite detailed and thorough regarding the connections going back to the days of Marcus Garvey. Don’t forget, the early Japanese who came to America were not in much better shape in the American experience than African-Americans at that time or anybody else who was not basically a WASP. So there were a number of instances where people bonded together. Kearney documents a lot of times where Japanese got involved very actively, from Garvey’s time right on up to the Second World War.

And this, in turn, was reciprocated. For instance, when novelist Richard Wright was in his heyday — Native Son had been published and he was being celebrated everywhere—he wrote this book called Twelve Million Black Voices, which most people don’t know about. It’s a photo book. Wright just wrote the essay to accompany the photos. There’s one paragraph where Wright essentially congratulates the Japanese for standing up for their rights. This was the time when the Japanese were going into Asia and calling it the Greater Co-Prosperity Sphere, and it was seen by Wright and a number of African-Americans as a good thing. Here were some people of color trying to claim their own destiny in the world. That single paragraph, which unfortunately reached publication just after Pearl Harbor, set the whole FBI investigation into Wright into motion, which many people believe culminated in his death in 1960, over twenty years later.

There was this whole thing of people who had anything to do with the Japanese, anything to do with anything that wasn’t very American, especially during the forties, which we wanted to include in the film. Another man in Chicago had this organization called the New Ethiopian Party and was actually tried and convicted for sedition and went to prison for the rest of his life. There were Japanese connections in all of this. It was not solely an African-American experience. There’s a famous photo of a guy named Kagawa and W. E. B. DuBois; he brought DuBois to Japan and introduced him to Japanese society.

These kinds of things were not well-documented or well-known, but they were happening all the time. There was, in this sort of intellectual, maybe high-brow Japanese society, a kind of affinity towards African-Americans and their struggle in America because at that time the Japanese, not being in such a different economic or social strata themselves in the world scene, saw a connection between people of color struggling to achieve and their own struggles in Asia.

But there were nonetheless painful ironies in the U.S. around that time. Maya Angelou, in her book I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, writes about how African-Americans moved into the former Japanese-American neighborhoods in San Francisco as they were cleared out for the camps. And she underscores the irony of how southern blacks, who through wartime employment opportunities on the west coast were being liberated to some degree, took over the homes and storefronts of the dislodged Japanese-Americans without understanding their shared oppression at the hands of whites.

True, but if you look at downtown L. A., what was called Little Tokyo then, a much larger Japanese-American community, you see the opposite. On a typical block where, say African-Americans moved into three or four homes where Japanese-Americans had lived before and then the rest were left unoccupied, whites came through those neighborhoods and looted and many times burned those other homes to the ground. Whereas the African-Americans moved in, took care of the homes, and in many cases — this is documented — when a Japanese-American came out of the internment camps, moved out of the house and gave the people back their house again. Or in some cases, if there was a Japanese-American neighbor and no one took that house, if it was empty and the black people knew the whites were going to come and burn it, they stood out there with their own pistols and said get away from this man’s house. There are incredible connections between African-Americans and Japanese-Americans, but you see they’re all on a personal level, not this huge, diplomatic, make-the-headlines level. But sadly, many Japanese-Americans considered the internment such an affront that they never returned.

They were too ashamed to go back to their homes and farms. And thus the migration began that we see today, with Japanese-Americans in many other parts of America and also back to Japan, the ones who went back or who were sent back and never returned. Which brings to mind one time when I did a presentation at the Rotary Club in Tokyo in the early phases of the Doubles project, when I was looking for support. The guy they’d hired as my interpreter turned out to be American-born, but during the internment he had been kicked out because his parents were considered subversives. He grew up the rest of his life in Japan, for a long time being treated very much like an outsider. But he stayed, married, the whole bit. And as I was giving my speech about intercultural children, this man, in the middle of his translation, broke down and started crying. We stopped the speech so he could gather himself. The audience didn’t know what was going on. It took about ten minutes for this guy to gather himself enough, then he said, “Daijobu, I can do it.” So I finished the speech and he was so embarrassed and told me, “Listen, I feel so terrible about what happened, but your speech hit me in a place I haven’t visited in fifty years.” And then he told me his story, and how all these years he’d put it away. So now here he was, an older guy in his late fifties, and he thought, “I’m a Japanese.” But my speech reminded him that no, he was still not quite a Japanese. I never saw him again. I thought he might stay in touch, but I could see this incident was the purge that was needed, and I guess he got back on the crowded train, went home and resumed his life.

When and how did you get the idea for Doubles?

While making Struggle and Success and interviewing quite a few African-Americans who had married Japanese, I met many of their children. Here were kids who had grown up speaking two languages, who’d been shaped by two cultures all of their lives. And there were so many — not only the children of African-Americans, but of all kinds of American men and women who had married Japanese partners, and for that matter, children of foreigners from all over the world.

I soon learned that in Japan, such kids were commonly called haafu, or “halves.” To me, and to many of these kids and their parents, this term seemed to suggest that these children were not quite whole or complete. But in pre-camera interviews it soon became clear that many of these kids had twice the culture, twice the heritage, and twice the language skills. They had more, not less. And many of them had a strength and courage that came from their daily struggle to define themselves — not so much to find their identity as to create it.

So what goal did you initially set for yourself with this film?

I wanted us to look through the eyes of children who have had to come to terms with two radically different cultures while at the same time trying to express one hundred percent of who they are as individuals.

And once again, you dug into the history.

Yes, in particular the story of the American military occupation of Japan following WWII, which produced the first large number of mixed children. Some were born to married parents, others out of wedlock. Some grew up in America, others in Japan. It was hard finding sources, but as I got deeper into this history I found myself wondering why the stories of these children, and the adults they’d grown into, had so seldom been told. Even before our camera started rolling I knew we’d found a rich chapter of oral history, the human story that continued after the war’s end.

Why do you suppose this was under-reported?

I think the answer may lie in our nature. For most of us, what we know or do not know is actually less important than what we do not want to know. A truthful history of Japan and America’s intercultural children makes us face the pain and shame of abandoned children, and epithets like ainoko [love child], which was much worse than “half.”

But you also uncovered some heroes.

Yes, like Sawada Miki, a brave woman who opened her home to scores of abandoned kids. Fortunately, even in the worst of times there were people who reached out to these children with love and compassion, who made real sacrifices to help them. That’s vital for people to know. But this was an agonizing period. One could overlook it and simply enjoy telling the stories of more recent times, when children of mixed heritage have become a source of pride to Americans and Japanese, when they’ve come to be seen as bridges between our two countries. But that wouldn’t be the total story, and would actually ignore the achievement of getting to where we are now. Still, we have further to go. Even today it’s not easy being so different, not in Japan or in America. Each society, in its own way and to different degrees, values conformity or uniformity. We Americans speak a lot about multiculturalism. But in my experience most Americans still look at you based purely on race, not culture. They’ll blindly cross-out a whole side of your heritage. This makes it hard for “doubles.” If you’re dark, you’re an African-American, no matter that your mother or father is Japanese. And if you look Asian, then that is what you must be, no matter that one of your parents is Caucasian. It’s a painful irony that many “doubles” in America feel that, at least in public, they have to “pass”— to fit into the narrow category society offers them, instead of openly affirming their intercultural identity. Many Americans have trouble accepting that you can be two things at once — that you can be “double.”

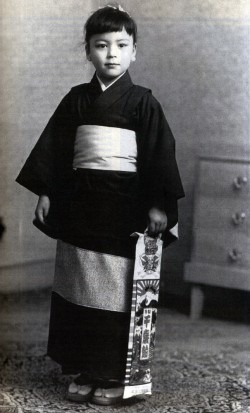

In Japan, on the other hand, the buzzword is internationalization, or kokusaika. And while Japan clearly has a long way to go, the word “half” at least recognizes that these intercultural children have, along with their foreign culture, a Japanese part as well. One privilege an intercultural child has in Japan is that they can experience Japanese culture. No one is going to deny them that. They may not be accepted as a full Japanese, but nobody will say they can’t participate in shichi-go-san [a ceremony for children aged 3, 5, and 7], or even the subtlest elements of Japanese culture.

I don’t mean to suggest that all the problems have been solved for intercultural children in Japan. My film makes it clear that they haven’t. But most of the kids I interviewed for Doubles were really happy about the way they are. What makes them unhappy is having to make the world understand who they are, and having so few opportunities, in fact, to do that. After getting to know lots of doubles, I’ve come to feel that the future is theirs. They have the most to teach us about crossing cultural boundaries, something which more and more of us will have to do in the years ahead.

Was Doubles easier or more difficult to make than Struggle and Success? Did you feel that you had more distance from your subject, and did that make it easier or more difficult to make?

Doubles for me was only more difficult because of funding. Unlike Struggle and Success, where for the first time in my life I had all of the budgeted funds before I started shooting, Doubles, because of the sagging Japanese economy, was a return to that world that had once driven me out of documentary filmmaking, of the fundraising nightmare.

I enjoyed making Doubles, meeting the people, and the creative process. The part that was not enjoyable was going back to begging again to get support. It’s been that way with the new film as well. When you reduce the filmmaker to a beggar, something suffers in the process because you can’t just focus on the movie. You’ve always got to think, if I write this check will it bounce? But aside from finances, some work on Doubles, was easier because Struggle and Success had been received well. People said, okay we know what you’re capable of. And in Japan that’s the biggest hurdle, just to get to that place.

Also, it was your second time working with videographer Shimazu Hisazumi and his team.

Which is always wonderful. These guys go the lengths of the earth for me. Right now, in fact, Mr. Shimazu is tracking down an antique Japanese music box so that I can cover one shot in my new movie that I’m not even sure is going to make it in, but because I wanted it he said, “Don’t worry, I’ll find it for you.”

That’s the side of Japan that’s so hard to convey to people back in America.

Right. He just knows my work, that if I’m looking for something there must be a good reason. But despite the best intentions, documentary filmmaking itself does boil down to money. You need support so that every time you make a film you don’t have to start at letter A again and do the research out of your own pocket, which is what I had to do on this latest project. The funding came after most of it was done and you can’t just say okay I’ll reimburse myself, because by now that money has to go to something else.

Other documentary filmmakers have told similar stories, about massive credit card bills and all kinds of financial troubles.

Oh yeah, and when you get this knee-deep in production, like where I am right now, I’m not even looking at the bills. I just put them in a pile, just praying every time I write a check it gets paid and I don’t have an irate person screaming at me who has worked all night long and not slept and missed part of their holiday this year because of my project, only to have their check bounce. So it’s incredible pressure, and I think the Japan experience, going back to Mr. Yamada, has made me a much more caring producer with everybody I work with now. You feel like these people are your family. Right now this is my family, and I’m the head, and I have to make sure that they’re clothed and fed. It’s that kind of responsibility, and you don’t make what I call the quick American decision, firing people because something doesn’t go right. I’m now more in that Japanese setting where, if there’s a communication, thinking, or procedural problem, you know, let’s work it out.

You’re identifying this aspect of yourself with Japan.

Well, you observe in Japan how conflict is resolved, and it’s not the typical, American-style “I’m taking my baseball and bat and going home” or “It’s my way or the highway.” I realize that such problems do come up in Japan, too. There are all those English teachers floundering around these days who came over with signed contracts but have no income or anything now. That can happen anywhere. But I enjoyed a time in Japan when the rule was you didn’t do that to people. If you brought somebody in, you took care of them.

In making Doubles, did you meet any intercultural offspring with serious identity confusion?

I don’t know if there was anybody that consented to an interview that had serious identity confusion. One guy in the film, as he was taking me back to my hotel in Hokkaido, reached over to the back seat of his car and pulled out a New York Yankees baseball cap. He put it on and looked me in the eye and said, “I’d really like to go to America one day, but I probably never will because I can’t speak English and I don’t even know that part of myself. But I know it’s in me.” And there was something about how he said that which made me see very clearly what incredible pain a lot of these people feel in this kind of neither-nor experience that they are having to live. But I think if there were people who were having really serious problems, I didn’t get to talk to them, or they would decline to be interviewed. There were a lot of people that had basically buried their life, because they were not going to be accepted by Japanese. But there wasn’t much they could do since Japan was their first culture, their only culture, their only language. And they essentially passed for Japanese. One guy only agreed to appear in shadow. But there were others who wouldn’t even do it in shadow. They were like, “I can’t talk to you about this. I can’t revisit that. Now I’ve found this little niche and I’m going to work this because I can’t go to America, I’m not an American. My father might have been an American once and so on, but who am I? I’m a Japanese.” They couldn’t take the journey with me.

The man in shadow did seem to speak for them. But I was wondering if there were legions of people like this?

Maybe not legions, but there are more people “passing” in Japan than there are people openly proclaiming their dual heritage. If you could pass as a Japanese in that society it’s much more to your advantage to do so.

The Japanese version of “high yellow” (a term once used for light-skinned African-Americans), with a touch of irony on the color?

Well, yeah. And on the other hand, there are thousands of families all over America who, if they dared to check the records, would be shocked to know that they’re black. It just makes life easier not to deal with this, so why, like the weeping interpreter at my speech, why visit something that’s going to dredge up these uncomfortable, hurtful feelings? You can pass, and though it’s not the truth, it’s better than a nightmare.

I realize that you’re a filmmaker and not a sociologist or anthropologist, but given the kind of films you’ve been making I feel compelled to ask: to what degree do you think culture defines identity?

I think to a huge degree. It’s not the only factor, but an underestimated one that largely determines who we are. It can also be a troubling factor because the dynamics of color as they’ve been orchestrated all over the world make it uncomfortable for people to be something that’s not part of the ruling class. As you say, I’m not all of these ‘-ologists,’ but in my own experience it has become a defining point for me, to realize and understand who I am once I examine my life through the lenses of the cultures I’ve experienced, and not through this limited viewpoint of my supposed ‘place’ in American society because of my phenotype.

What does phenotype mean?

It’s one of these fancy ‘-ologist’ words for color. I learned that during the process of making Doubles, when I was interviewing all these people who lecture and write. That’s the term they prefer.

Is race also an essential building-block of identity?

My feeling is that we are who we are by means of culture, not by race, and we’ve all got to start getting to that page in the book. If we keep playing this other game there’s no way out, and we will only dismantle ourselves. Race is a very poorly-used tool in the world. I really don’t subscribe to the notions of race anymore. And this is not naive on my part; it’s just that if no one else wants to start this tone, I will.

Japanese people often tell me they’re trying to reject parts of their culture. How about resistance to one’s own culture? Can one reshape one’s identity in such a way? And if so, to what degree?

To the degree that you are comfortable with. You can go as far as you want with your experience or just take it a little ways. I’ve met people, particularly people of color all over the world who, just for the sake of survival and ease with life have completely adopted the cultures where they are living, whether it be Europe or Africa, wherever, because it just fits better. And they don’t feel strange speaking with new accents or doing the things they do or thinking the things they think. It’s only when they come back to America to see family that they have to switch back to the apartheid world of America. And that’s when they realize how different they are from their friends. But in their day-to-day life in the countries they live in this is quite natural to them, nothing abnormal. To me, it’s up to the individual. I’ve met people in all walks of life, all creeds and colors living in places around the world that are not the countries of their birth. And sometimes if you didn’t ask you wouldn’t know. They’ve become a part of that world now, and that’s home.

How about you? You hinted at this a few moments ago. With a total of four years’ experience of living in Japan, to what extent have you traded in your cultural values for Japanese ones?

Well, there’s a general civility. This is something one has to respect if you’re paying attention in Japan and coming out of the American experience. Most Japanese, even when situations don’t really warrant it, attempt to be civil when they try to resolve conflicts. That’s something we can all learn from. We’re always going for the jugular in the U.S. It’s such a winner-take-all kind of mentality. The idea of compromise is like a defeat. But it isn’t. The hard lesson to learn, and I didn’t learn it easily and I don’t think any foreigner in Japan does, is that it is not always necessary to be right. Sometimes losing, in the sense that a Westerner would see it, you win more.

Can you explain how your current project, After America . . . After Japan evolved, how you came around to doing it?

When I went on the road showing Doubles I was aware that I already had a bit of an audience waiting. But I found that this audience had grown, because not only were there people who had known Struggle and Success but this new group who, once they’d heard the subject matter of what I was now exploring, just came out. And many of these were, in fact, people that I have since featured in After America . . . After Japan. They were not doubles themselves, but nationals of the country where they now lived, either America or Japan, but because of their experience in the host country they too felt double. They could identify with everything these “mixed” people were saying onscreen. That’s what kicked the ball off, and that’s when I began to say this is really curious, that these people who are supposedly “pure” Japanese or “pure” Americans don’t feel like that anymore. They are sensing an affinity towards these people in Doubles who are clearly interracial and intercultural.

Frankly, that was my response to Doubles too.

Yes, well that’s what got the new film going, these people saying, Wow, I never thought about it through the prism of culture. I was just looking at it as this is my life, never evaluating it on that level, but now I think this “double” idea is a good way of understanding what this is all about. And then once you start to explore that, it dawns on you, okay, now I see what we’re all going though.

Do you feel, then, that you’re circling back towards yourself with this new film? Is this about as close to yourself as you’ve gotten?

Yes, in many ways. It’s paralleling my own experience because I am still in the process of return, a stage which has me reflecting on my childhood. I grew up in America when many parents tried to shield their children, especially children of color, from the harsh realities of society. They were trying to take in the benefits of integration and opportunity at the end of WWII. People just didn’t want to go to places that might cause their child not to be empowered. I was placed in that fast track. I imbibed all the values of the kids around me, most of whom were Jewish, and that was my experience. So, it was only at times of family gatherings when I was reminded of the other part of me. In the mainstream at that time, which was the educational system, I was one of the kids in school. My friends were Bob Shapiro and Amy Schwartz and Lou Steinberg.

Good Jewish names. And I guess every year on the High Holy Days you were one of the few kids left in the classroom?

Right, or the only African-American kid at the bar mitzvah, and how do I put this thing on the back of my head? And looking at the world through your cultural prism, in terms of Jewish mysticism and all of that . . .

Was that prism or prison?

Ha, ha, ha! I said prism! I don’t want the JDL [Jewish Defense League] coming after me. But do you know what I’m saying? And then in the university this continued for me, because at Tufts there were lots of Jewish people. Jewish friends helped me get into Tufts. But then you meet other African-Americans who grew up a little differently than you. And that was quite an eye-opener, and then I was off to West Africa, and then back to America, and then Japan, and again to America. So there’s all of this cross-pollenization constantly happening in life, but in America we’re trying to fit you in this box! This is where you belong!

Now that the editing of After America . . . After Japan is complete, can you point out any unanticipated lessons you learned from the film?

What has strongly emerged is the importance of children in the life of those returning. In both parts of the film it becomes evident that once the sojourner has taken the step to produce a new generation, be it a mono-cultural or intercultural marriage, then the issues of the sojourn, whether to return “home” or stay put, come to the forefront. In the “After America” portion, the main character, who lived in the U.S. for nine years, really only changes as a man after he becomes a father. He goes from being single to married and then to having a family, and suddenly the issues of his being chonan (eldest son) back in Japan become evident. Also in the “After America” portion, a Japanese couple faces a crisis with the wife’s pregnancy in the U.S. This story just popped out during the on-camera interview. In pre-interview, neither husband nor wife talked about this crucial time, but they make clear that it was a test of their marriage, their sojourn in the US and the power and importance of American friends and colleagues. They came out of it incredibly stronger as a couple and it’s clear to me that the incident was a defining moment in their lives.

On the flip side, in the “After Japan” portion, an American returnee comes home because — he finally admits on camera, totally unrehearsed — that he just did not trust the Japanese medical system to deliver his second child after a very trying time in the birth of his first child. This primal response towards caring for the next generation clearly emerges in both parts. As adults we can make all kinds of choices, but when it comes to issues of family, that original sense of who we are and how we were raised comes out.

You seem careful in your documentaries to present the bitter with the sweet in as accurate a balance as you can manage. What sorts of benefits, then, have returnees realized upon their return to their home countries?

People come back and they have to sort it out in the beginning. But once they’ve done that they find a way to celebrate what they’ve learned abroad. They find a place in their life where that American experience, if they’re Japanese, gets a chance to stay alive. Maybe they can’t do things in a big or very showy way, but in a small way they can celebrate that part of themselves that still very much exists and that they want to exist throughout the rest of their life.

Are the readjustment problems of returnees universal or not, and is there a distinct difference between Americans and Japanese?

It’s not universal, and yes, there is a distinct difference between Americans and Japanese. Most Japanese go abroad with what I would call a “leash” on. There is the sense that one day someone in Japan will tug and you will come back, be it company, family, or some sense of traditional responsibility. Most Americans, though, leave America with nothing around their neck. You can stay as long as you want. And except for certain business people or diplomats, it’s your decision when or whether to come home. So that makes readjustment a different experience.

Let’s turn one last time to the subject of money. Television is for most who work in it such a lucrative medium. How do you come to terms, then, with working so hard in a genre of TV where even making ends meet is nearly always a problem?

Well, that’s a very good and tough question. One thing that I have to decide as an artist living back in America now is how I can support these efforts in the future. Obviously I would like to continue to make these kinds of films. I can see people enjoy them and are affected by them. But by the same token there’s a big cloud looming over my head. Yesterday I was on a television set shooting a commercial program because I still have to do that kind of work to do this work. To finish these documentaries, if you don’t have the whole budget the first thing that gets cut is the producer’s salary — my salary. The only way I can continue is to take on other work that takes me outside of this project for awhile. And as I said before, this challenges you to maintain your focus. Then there’s the bridge you get to at the end of one of these projects: Will I be able to do this again? Because you know all the constraints you’re up against. So it’s hard to answer this because I don’t have somebody waiting with a pot of money.

What is next for you, though? Is your next film beginning to take shape in your mind?

Very deliberately I am not thinking about another film. These three films will have comprised, in the end, seven years of my life. They’ve been great, but tough too, especially making these last two films. I’ve got to take some time out to focus my attention on some other areas of the business, such as distribution, and trying to look at this organization, Global Film Network, that has evolved as a result of these three films. I want to promote the new film, but also promote the organization. There are filmmakers I’ve met who are doing similar work or would like to. I want to try to find more people around the globe, and through this coalition of filmmakers and artists, to begin to rethink this whole idea of funding and support, new media, new technology, so that there is a plan for the future and we’re not just simply, as I’ve been doing, cranking out project after project, with hardly a chance to look at where we’re going.

Do you think Japan will be a part of you for the rest of your life?

Without a doubt. This experience couldn’t have come at a better time, or made a deeper impact. And it would still be a very big part of my consciousness every day whether I were making these programs or not. Once you give in to Japan, let go and let Japan have its way for awhile, there’s no way you can ever escape completely. There’s a wonderful richness in Japanese culture and in Japan as a country, in all of its uniqueness. You can learn and grow from it. There’s a lot wrong with Japan, too, and everyone can agree on that, but there’s also a lot right. So why escape?