“Nineteen sixty-nine was the year student uprisings shut down Tokyo University. The Beatles put out The White Album, Yellow Submarine, and Abbey Road, the Rolling Stones released their greatest single, “Honky Tonk Women,” and people known as hippies wore their hair long and called for love and peace. In Paris, De Gaulle resigned. The war in Vietnam continued. High-school girls used sanitary napkins, not tampons. That’s the sort of year 1969 was, when I began my third and final year of high school. I went to a college-prep high in a small port city with an American military base on the western edge of Kyushu.”

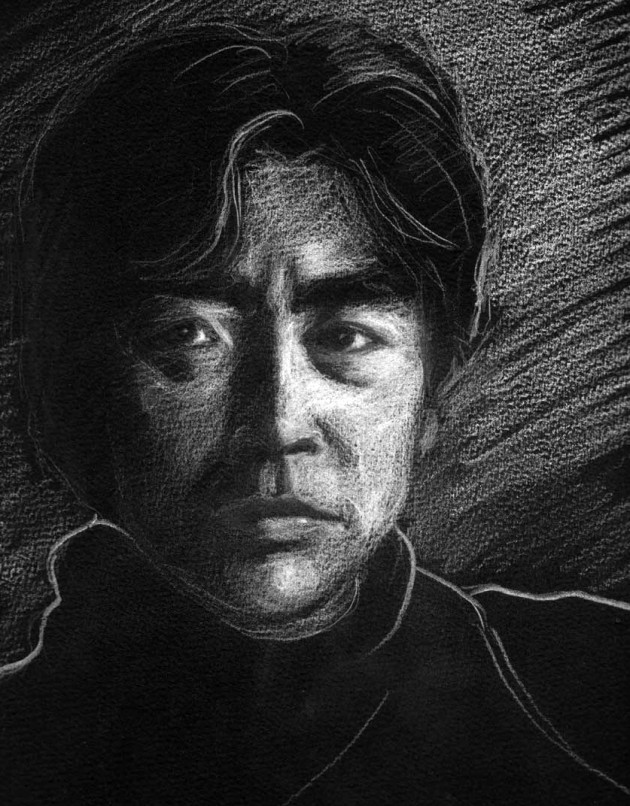

[I] first met Murakami Ryu in 1993, I think, when I was translating his novel, 69, which begins as above. We’ve worked together on a number of projects since then, and whenever I’m in Tokyo I try to meet up with him. He’s usually kind enough to make time for me (and, typically, to treat me to an extravagant meal at the fancy hotel in Nishi-Shinjuku where he spends a good chunk of each month writing and doing business). I was hoping to interview him for Kyoto Journal when I was in Tokyo last September. Ryu graciously agreed to the interview and even brought (at my request) a small tape recorder. But as we sat facing each other in the hotel’s Japanese restaurant, I suddenly remembered something: I’m an idiot. I can barely hold up my end of a conversation even in English. I’m going to interview a world-class literary genius for a serious publication? In Japanese?

Ryu seemed to realize the unlikeliness of it all at about the same moment. He turned off the recorder and graciously suggested I have the editors e-mail him some questions, to which he promised to respond. I breathed a sigh of relief, asked for more beer, and started whining about my latest failure to establish a steady girlfriend.

Now it’s a couple of months later, and I have the results of the e-mail interview. Whoops!

Kyoto Journal: Your narrator in /69 seemed to think 1960s rebellion was simply a prank, a childish scheme to attract women’s attention. Do you share that view?

Murakami Ryu: You mustn’t naively believe everything you read in a novel.

Sorry! But we do tend to do that, don’t we, especially with novels and stories that are blatantly autobiographical. Here’s the beginning of “La Dolce Vita,” the first in a series of linked stories in Ryu’s Cinematheque(1995).

I was about 23. Enrolled in a college of fine arts. Thinking back on it now, I’m not sure why I’d chosen an arts college. It’s true my father was an art teacher and I grew up watching him paint, but I’d never seriously considered becoming a painter myself.

I guess I just wanted to keep the money coming. If I hadn’t entered some college or other I’d have lost my allowance. For two years I was what this society calls a ronin, but the life I’d led, near the American military base at Yokota, was worlds away from that familiar image of the struggling “lordless samurai” student cramming for his next crack at university entrance exams. I’d been living with an older woman, hanging out with GIs, doing every drug known to man, and getting myself arrested on suspicion of various crimes. It was a totally immoral lifestyle, but I can’t say I ever derived much pleasure from it. Seems as if I was choosing, with unfailing fidelity, to make only the worst possible choices.

As autobiographical fiction, Ryu’s Cinematheque fills the gap between 69 and Almost Transparent Blue, and the style is somewhere between the flippant frivolity of the former and the dark obsessiveness of the latter. Almost Transparent Blue was Ryu’s debut novel. Published in 1976, when he was 24, its success rocketed him from obscurity to fame—or infamy—virtually overnight. More than 25 years later the book, with its graphic descriptions of sexual orgies and voracious drug use, is still shocking to read.

You won Japan’s most prestigious literary prize with your first novel, which you wrote while still an art school student. The book sold millions of copies, but it also polarized people: many were repelled by it. What was it like to have that kind of impact and success so early?

Ryu: For me, the biggest thing was that I became financially independent.

Ryu used his independence well. Being a man with a tremendous appetite for life, he began living large, traveling the planet and savoring its various pleasures. But he also began what has already proven to be one of the most prolific and multi-faceted careers in literary history. In 1980, Ryu published what many still consider his masterpiece, Coin Locker Babies, a novel that became a sort of bible for Japanese punks and other disaffected youth but was also an enormous critical and commercial success. Its opening sentence (“The woman pushed on the baby’s stomach and sucked its penis into her mouth….”) is now probably one of the best-known sentences in all of Japanese literature.

In a conversation with the novelist Steve Erickson a few years ago, Ryu explained what had inspired him to write this book:

“In the years before I started writing it, there were several cases in Japan where babies were abandoned in coin lockers. Most of these babies were already dead, and the parents or whoever were just looking for a place to dispose of the corpses. But some of the babies were still alive, and a few even survived. Now, what if these babies grew up and found out that they’d been abandoned like that? Wouldn’t it be easy for them to build up a tremendous hatred for the world? Wouldn’t it be easy for them to want to destroy it?”

When the Aum Shinrikyo cult unleashed a sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway system in 1995, many commentators saw Coin Locker Babies as having predicted something of that sort, and suddenly the establishment was listening. “For all these years I never got myself to fit into the mainstream society,” Ryu told the Wall Street Journal, “and now people in the center of the mainstream want to hear what I have to say.”

Twenty years ago, in the novel Coin Locker Babies, you wrote about two abused and abandoned children. Nowadays in Japan, we hear news almost daily about parents who abuse and even kill their babies or children. At the same time, we read more about bullying and brutal killings committed by young kids. What is happening to this society?

Ryu: It’s not that something is “happening” so much as that things which have always gone on in society have started to come to the surface. Child abuse and the cycle of violence are worldwide problems, not things that happen only in Japan.

You have an astonishing ability to create utterly bizarre or outlandish characters who nonetheless seem absolutely believable and real …. How is it that you’re able to make such characters so easy to identify with?

Ryu: Beneath the level of consciousness, we human beings have an entire universe of darkness and chaos. The rational faculty is only one small part of us. We try to control the dark parts with laws, morals, common sense, and so on, but human beings are too deep, diverse, and free to be contained by such things. Novels can sometimes depict the struggle between reason and the darker regions of the heart.

In 1988 Ryu published Topaz[excerpted in KJ 10], a collection of stories told from the first-person points of view of young female prostitutes, most of whom specialize in S&M. Here’s a sample from one of the milder stories, entitled “Eggs.”

I pressed the chime at the room I’d been sent to, and a man in his fifties opened the door and was kneeling there naked saying, “I’m at your service!” I took the envelope he was holding out to me. There was 50 thousand yen inside. I’d seen this man before. He was an “M” who managed a vinyl factory for a company in Kobe and liked high heels and underarm odor. He said, “I had the honor of making your acquaintance at a party.” At the end of the year doctors and businessmen and people like that have a lot of parties. I often get called to parties for businessmen from Osaka and Kobe.

After the man had taken two dumps and come twice he scowled and spat phlegm into a flower vase and called somebody who I guess works for him. “It’s me. What’s the deal on those futures? Tell Kikuchi to send in an order from London. Not by telex, tell him to call it in ….” As he was talking he looked at me. Now that he’d shot his wad, he just jerked his chin, signaling me to leave, as if I were a dog or something. This was the same guy who, the first time he came, was crawling around on his hands and knees licking it up. It takes all kinds. Some stay on their knees, bowing to you, from beginning to end.

Topaz created another big stir in Japan. And Ryu, who had been directing film adaptations of his work since the early 80s, decided to use these stories as the basis of the script for his next movie. The result, entitled Topaz in Japan but Tokyo Decadence everywhere else, was a sensation at film festivals around the world and remains a cult favorite in Europe and the U.S.

In addition to writing books, you’ve worked in radio, TV, and cinema. What have you learned from your involvements in Japanese popular media?

Ryu: I think the distinction between “academic” and “pop” is more or less meaningless. I haven’t learned anything in particular from working in TV and film.

Can a writer be a media celebrity and maintain his creative work?

Ryu: I’ve never once thought of myself as a “media celebrity.” I become involved in TV projects and what not only when the subject is of particular interest to me.

One critic has written, “The primary concern of Japanese literary hotshots Haruki and Ryu Murakami (no relation) is America. Not necessarily America the chunk of land across the Pacific Ocean, but America the cultural influence, America the trendsetter, America the quiet infiltrator of the East.” How would you comment on this?

Ryu: After World War II, a tidal wave of American culture swept over Japan. It would not be possible for anyone growing up here to be free of this influence. That’s true for people of other countries in Asia and Europe as well. Since I came to know Cuba, however, my interest in America has changed — in complex ways that would take too long to explain here.

I think Ryu started going to Cuba in the early 90s. As happens to many visitors, he seems to have been immediately captivated by the energy of the place and by the incredible and ubiquitous music and singing and dancing. For years now he’s been bringing Cuban musicians and groups to Japan for concert tours, recording them for his own record label, and using their music in his films and TV documentaries. His 1995 film Kyoko was shot in Tokyo, New York, various locations on the road to Miami, and Havana. Kyoko, in Ryu’s original screenplay and his subsequent novelization, is an orphan who as a little girl was given hope and courage, along with lessons in rumba, mambo, and cha-cha-cha, by Jose, a Cuban-American GI. Kyoko grows up to become a beautiful young truck driver (played by the beautiful Takaoka Saki) who has finally saved enough money to go to New York to try to find Jose and thank him for teaching her to dance, which she feels literally saved her life. She finds Jose eventually, but he’s dying of AIDS and has no memory of her. Kyoko volunteers to drive a van bearing Jose and all his life-supporting medicine and equipment, all by herself, all the way down to his family’s home in Miami, and between adventures on the road she tries repeatedly to jog his memory. I for one am incapable of watching the moment when his memory clicks in, without quietly sobbing (this though I translated the words myself—most of the dialogue being in English). “Kyoko!” he says. “You grew up!”

Kyoko, produced by Roger Corman, was released in Japan in 1995 and became Ryu’s greatest domestic success as a filmmaker, but the film wasn’t released in the U.S. until four years later, newly titled Because of You. It’s worth checking out if only for the music, boasting as it does an amazing soundtrack of Cuban standards performed by top Cuban artists. And the footage from Havana includes an elderly couple dancing a son that has to be seen to be believed.

Sharply contrasting the sweetness and sentimentality of Because of You is a recent Miike Takashi film based on a 1997 Murakami Ryu novel entitled Audition. At this very moment, thousands of people are watching Audition at theaters thoughout the United States. And they are all, I promise you, shrieking and freaking. Here’s just the beginning of the novel’s horrifying climax:

“You can’t move.”

A shadow behind the curtain shifted slowly, and when Yamasaki Asami appeared Aoyama thought he was hallucinating. Long time no see, he tried to say but couldn’t produce the words. All his senses were numb.

“Go to sleep for a while. I’ll wake you when I’m ready.”

Asami walked over to him and pinched his cheeks together with the thumb and index finger of her left hand. She was wearing surgical gloves. Aoyama’s mouth sagged open. She squeezed tight, her fingers digging into his cheeks, but he felt no pain. All strength was gone from his muscles, and drool spilled from the corners of his mouth. She held up a very thin plastic syringe for him to see.

“Your body will be dead, but I’ll make it so you can still feel everything. It’ll be a hundred times more painful that way. Get a little sleep while you can.”

She inserted the needle under Aoyama’s tongue.

Many of your characters are sick, damaged people searching for meaning in a society that is increasingly materialistic and shallow. Do you identify with these characters?

Ryu: Every society has people who can’t adapt, and their “sickness,” if you will, their inability to adapt, can hold a mirror up to that society. But some of my more recent novels, like Exodus from the Land of Hope and The Last Family, are not about sickness at all.

You wrote in Murder in a Lonely Country (an extended essay published in a Japanese-and-English bilingual edition) that “There has never been a Japanese person since the begining of our history who has experienced the kind of loneliness enveloping the children of today,” and you clearly attribute this emotion to the end of modernization. What can be done for these children?

Ryu: The important point is precisely that you can no longer neatly categorize “Japanese children of today.” Japan is a country where group consciousness became so highly developed that “loneliness” was not a concept that existed for any but a very few, marginalized individuals. Just knowing what loneliness is, therefore, is progress of a sort.

You’ve written that the focus in Japan has shifted from the national to personal goals, from the group to the individual. But what about the individual’s role within a community? Is there a middle ground that’s missing here?

Ryu: For some reason, the concept of the individual didn’t exist in Japan. Maybe it was because in the rush to modernize, too much emphasis was placed on creating a sense of national unity, or maybe it was because of a lack of racial, religious, or linguistic diversity. But the question of “the individual’s role in society” can only arise if the society has the concept of “individual.” Since there is no such concept here, really, the question itself doesn’t come up.

You detached yourself at a young age from the illusion that the system would protect you. How did you come to that decision so early? What has it meant for you?

Ryu: I didn’t want to be protected by the “system” (by which I mean corporate employment and so on—I’m fine with being protected by the fire department and police), because the system asks for loyalty in return. Perceptive young people have always been able to see that the commonsense notion “the company will protect me” was in fact an illusion. With the repeated downsizing and restructuring of Japanese companies, even the illusion of lifetime employment is starting to disintegrate. In times of change like this, those who are quick to realize the truth—that the company will not protect them—have an advantage.

Ryu is genuinely concerned about Japan. I believe he sincerely wants to help people adjust in a healthy way to the seismic sorts of changes that are rocking Japanese society. When I met him in September, he brought me a copy of The Last Family, which had just come out and which, he told me, he was adapting as a TV drama that would begin airing in October. Ryu puts out books faster than I can read them, and inwardly I groaned. But when I got back to my hotel and read the first chapter, I thought it was really special. I saw in the story all the clear-headedness and compassion that Murakami Ryu projects when you meet him (his interest in you, his concern for your comfort and well-being, his modest affability, his regular-guyness when you’ve been expecting a wild man, his engagement with the world, his generosity), not to mention his uncanny ability to get under the skin of his characters — characters as outlandish as Yamasaki Asami or as ordinary as the crumpled salaryman next to you on the train—and to make them come alive. And the book has what Ryu calls “a positive, happy ending”: the four members of the household end up living separately, taking responsibility for their own lives and living as individuals, but in many ways more bonded than ever. So I called Kyoto Journal the next day and said I’d blown the interview but had a good idea for a translation ….

The first chapter of Murakami Ryu’s The Last Family was published for the first time in English in KJ #49, preceding this interview.

Author

Ralph McCarthy

Author's Bio

Ralph McCarthy says: I’m still trying to write songs, and have been working on bilingual editions of classic Manga — The Genius Bakabon, Akko-chan’s Got a Secret!. GeGeGe-no-Kitaro. I also have lots of Murakami Ryu stuff translated and waiting to be published. Come on publishers!

Copyright held by the author

Credits