One of Kyotographie’s charms for art lovers and tourists alike is the invitation it extends to enter unknown or off-limits corners of Kyoto. As the festival has grown, larger commercial and even industrial exhibition spaces have replaced machiya, temples, and other traditional buildings. Last year, the visitor’s center, closing party, and several exhibitions were held in the shell of the partially-demolished Shinpuhkan, (now in the process of becoming an Ace Hotel). This year, exhibitions are being held in the bowels of the Kyoto Shimbun’s printing plant and a former ice factory in the Tambaguchi Central Wholesale Market. As in years past, experiencing the festival is like being a guest at a vast, city-wide tea ceremony: upon entering, one goes to the tokonoma and plays the jeu d’esprit of trying to fathom the hosts’ intention, taking in the dynamic interplay of theme, visuals and settings.

Izumi Miyazaki, Hey, omachi!, 2017. Kyotographie 2018 Exhibition picture by Susanna Pavloska

This year’s theme is “UP.” As it just so happens, the festival’s final weekend coincides with the 50th anniversary of the student protests of May 1968 in Paris, an event that marked a major shift in consciousness for young people in various parts of the world, including Japan. Claude Dityvon’s monochrome photos of the uprising adorn the walls of this year’s Collaboration Plaza at the NTT West Building at Karasuma-Sanjo while Curtis Mayfield’s “Move On Up” plays in the background. In addition to the 15 main KG shows, there is a confusing array of KG+ Satellite Events, including Exhibitions, Associated Programs, 21 Award exhibitions, 5 Special Programs, and 7 Gallery Programs taking place in all corners of the city. In addition, there is a full program of artist talks and other events relating to the main venues, including sessions in English, French, and Japanese, film showings, music and dance, hands-on workshops, produce markets, and activities for kids.

At first glance, the overall theme does not seem to jibe with the spirit of the two biggest downtown venues, Lauren Greenfield’s “Generation Wealth” at the Kyoto Shimbun Building, and Jean-Paul Goude’s “So Far, So Goude,” in the Annex of the Museum of Kyoto. Greenfield’s retrospective of her work of the past 25 years depicting rich kids, oligarchs’ wives, and gold chain-draped rap singers (among many global phenomena) speaks to moral decline rather than uplift. However, after the global economic crisis of 2008, she sees her work as a “morality tale,” and has been moving from still photography to film-making because of the latter’s “greater reach” (the film of the same name that will premier this July on Amazon.) Goude’s exhibition is simply over the top: on the first floor, a selection of his drawings and photos spanning his long career run counterclockwise around the walls of the large room. Idol-like alligator-tailed installations rotate in the center, while strolling Marguerites in gowns, corsets, and beards of pearls, courtesy of Chanel Fine Jewelry, belt out “l’Air des Bijoux” at ear-splitting volume a la Bianca Castafiore, pausing occasionally to admire themselves in a mirror licked by infernal flames. Other rooms display Goude’s ad campaigns for Chanel, and the upstairs cinema plays films about Goude’s life and works in a continuous loop, attesting to his profound influence on pop culture. While not politically correct, Goude’s enthusiastic pursuit of his primitivist fantasies generates plenty of creative energy and he has probably done more than any other person to reframe black and brown women’s bodies from objects of ethnographic curiosity into objects of desire.

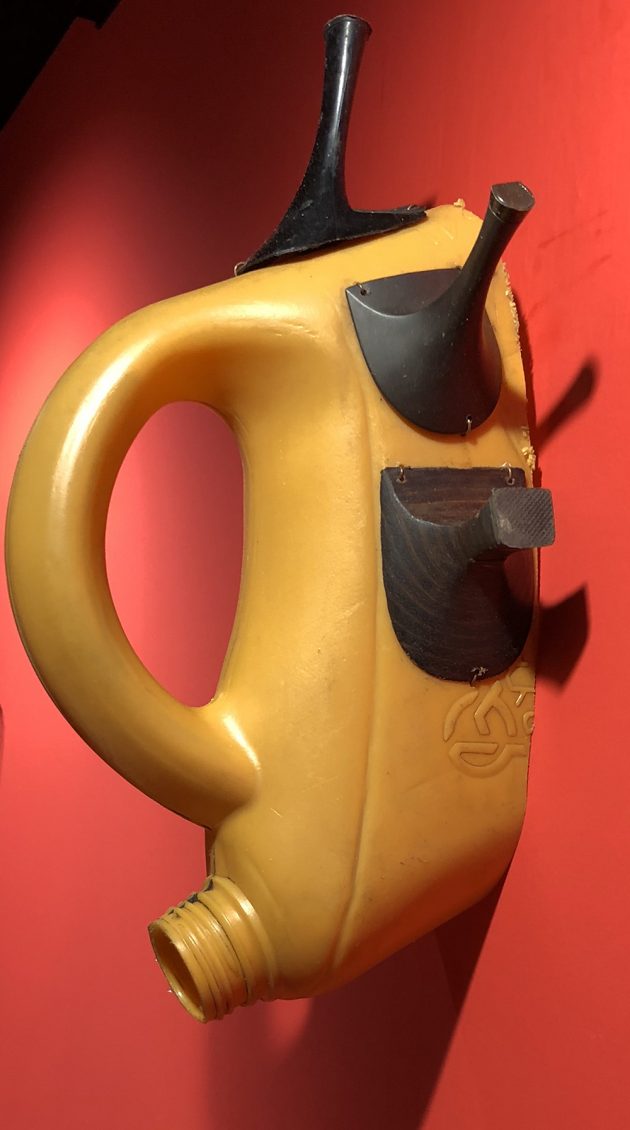

Romuald Hazoumé, passe temps, 2015. Kyotographie 2018 Exhibition picture by Susanna Pavloska

Goude’s primitivism is taken to task by Romuald Hazoume at the Kondaya Genbei Kurogura gallery on Shinmachi Street. At the entrance of his exhibition, “On the Road to Porto-Novo,” is a panoramic street scene showing ordinary Beninese going about their daily business, buying and selling Nigerian oil in 5-gallon glass jugs. On the second floor is a series of photos depicting bystanders watching a Vodun ritual, and a display of “primitive” masks of the kind so beloved by Picasso and his contemporaries – only these are made from the garbage that industrialized countries routinely ship to Africa, with the intention that they be shipped back to their origins in order to “save the real masks for Africans.”

Some of the other downtown venues include “Power to the People,” Stephen Shames’s documentary photos of the Black Panthers in Fuji Daimaru’s Black Storage. The presence of a white photographer at the heart of the movement testifies to its inclusiveness. His photos, which were suppressed by a mainstream press intent on demonization, show the group’s various self-help activities, including distributing food to the needy. While it can be argued that their legacy lives on in Hip-Hop, which combines the Black Panthers’s radicalism with Martin Luther King’s insistence on nonviolence, the two shows at the Horikawa Oike Gallery, Morita Tomomi’s “Sanrizuka – Then and Now” and Ono Tadashi’s “Coastal Motifs,” document the commandeering of land to build and expand Narita Airport and the erection of ugly and useless seawalls along the coastline affected by the 3-11 tsunami, seem to document a failure to speak up and be heard.

Fukase from Hibi 1991. Kyotographie 2018 Exhibition picture by Susanna Pavloska

It is hard to derive any sort of political message from the work of the other three Japanese photographers in the main festival. Kondaya Genbei Kurogura’s Chikuin-no-Ma is dedicated to the first retrospective in Japan of the work of important photographer Fukase Masahisa. Like many Japanese photographers, Fukase mostly disseminated his work through the medium of photo books and “maniac” magazines. The monochrome images in his photo book, Ravens (1986), which was recently re-issued by Thames & Husdon, is regarded as giving expression to the pessimism and despair of an entire generation. This show also includes a selection of vividly-colored photo montages from his early career as well as his drawn-over and otherwise embellished polaroids of himself and his cat, among other subjects. Strictly speaking, Nakagawa Yukio was known mainly as an avant-garde ikebana artist, but because of their ephemeral nature, the pairing of flowers and photography is a natural one. Katagiri Atsunobu’s tribute, “Flowers at their Fate,” highlights the fact that flowers are mortal beings that give their lives so that a work of ikebana can be created. In Nakagawa’s hands, flowers are seen as both the sexual organs of plants and mounds of bloody offal. Similarly, Tumblr darling Miyazaki Izumi, in her series of disturbing but cute self-portraits at the Asphodel gallery in Gion confronts gore and rice balls with equal equanimity.

Yukio Nakagawa, Fountain, 1988. Kyotographie 2018 Exhibition picture by Susanna Pavloska

This year’s stand-out venue is Sazanga-kyu, in the middle of the Tambaguchi Central Wholesale Market, located in the neglected corner of the city northeast of Kyoto Station. According to co-director Nakanishi Yusuke, the market is “dying” because of the growing tendency of retailers to source products online. Perhaps taking its cue from Tokyo Governor Koike Yuriko’s efforts to retain Tsukiji Fish Market as a tourist site, the City of Kyoto is developing the area, with plans to renovate the market over a period of 10 years and build a new train station and a 5-storey restaurant and hotel complex at Shichijo. Gleaming new public toilets and a “Sushi Ichiba” are already there, waiting for visitors.

Gideon Mendel, Drowning World, Jeff and Tracey Waters, Staines-upon -Thames, Surrey, UK, February 2014. Kyotographie 2018 Exhibition picture by Susanna Pavloska

Alberto Garcia Alix, Lisa at Buenos Aires, 2005. Kyotographie 2018 Exhibition picture by Susanna Pavloska

K-NARF, THE HATARAKIMONO PROJECT, wall in Kyoto City central Wholesale Market. Kyotographie 2018 Exhibition picture by Susanna Pavloska

The 3 main KG exhibitions at Sazanga-Kyu, Gideon Mendel’s “Drowning World,” Alberto Garcia-Alix’s “Irreductables,” and K-Narf’s “Hatarakimono Project,” all make brilliant use of the venue, a disused ice storage facility and a local barbeque spot, whose main customers until recently were people working in the market. Medel’s video installation, “Deluge,” as well as his stills of people looking into the camera from the drowned wreckage of their homes were taken over a period of 10 years in various places around the world that experienced catastrophic flooding as a result of climate change. The “dystopian, end-of-the-world” atmosphere of the abandoned facility, with its pipes and rusting machines and his collection of rescued family photographs is the perfect setting for this “exercise in empathy.” The facility’s second floor, which is reached via a crumbling concrete staircase, is the setting for Spanish photographer Alberto Garcia-Alix’s “submerged portraits” of street people in Madrid. Like Mendel’s portraits, they gaze out of their frames with quiet dignity. They not only don’t want to go to rehab, they refuse to be reduced to their various addictions, perversions, and transgressions against mainstream society. Next door, in the Kyoto Makers Garage, and plastered along the south wall of buildings 10 and 11 of the market, are K-Narf’s portraits of 100 Japanese workers. Unlike his fellow exhibitors, he does not consider himself to be a photographer but rather, an “artist who pretends to be a photographer,” with the intent of the “Hatarakimono Project” being to create a “visual archive” of workers’ jobs that will disappear in 25 years due to automation.

The Universe at my Feet, John Einarsen. KG+ Exhibition picture by Susanna Pavloska

As the main venues get larger and more diffuse in terms of media, it’s still possible to experience the spirit of the earlier days of KG through the KG+. The venues, though smaller, are just as varied; this year, they take place not only in machiya, cafes, and temples, but in a decommissioned elementary school, a hostel, and even a climbing kiln.

The photos in John Einarsen’s “The Universe at My Feet,” shown in the Jarfo Art Square in the Furumonzen Shopping Arcade from April 13-29, were taken while looking down during his morning walks and commutes across the city over the course of a year. He maintains that the clearest images “are made from a point of stillness and openness.” First there is a “flash” of perception, akin to the Buddhist idea of senyuukan, or seeing without bias. The result is an image that remains faithful to the moment of perception, as free as possible from “filtering and overthinking.” These are examples of Miksang photography which he has been studying for the past several years with Michael Wood and Julie Dubose. “Miksang” means “good eye” in Tibetan. Other examples of Einarsen’s work, along with works by Suzuka Yasu, Nakagawa Shuji and others can be seen in the group show, “Shitsurai; Offerings IV” at the Terminal Kyoto until 5/13.

“Lisa,” a dreamlike sequence of photos at a KG+ Award show at the Anewal Gallery, housed in a machiya in the opposite corner of the city, furnishes an interesting counterpoint to Garcia-Alix’s portraits. While shooting an interesting-looking building for his series, “Attractions Nocturnes,” on a street in Toronto, Nicholas Auvray encountered “Lisa” lingering in the frame. When she saw his camera, she started posing for him. Crossing the street, he spoke to her and learned that she had come from a small town, hoping to become a fashion model. Up close he could see that she had once been beautiful but now her body was covered with bruises and graffiti-like tattoos. Saying that she had now realized her ambition, she went away, leaving only her image behind (until 5/29).

Notable also is Karen Knorr’s “One Only, Only Once,” in Daitoku-ji’s Obai-in sub-temple (until 5/11). With many of these exhibitions open irregularly or closing before the main KG exhibitions, discovering these is both a treasure hunt and a race against time.

With its exhibitions and series of events in the Tambaguchi area, Kyotographie seems to be not merely bringing people to hidden or at least underutilized parts of Kyoto, but taking an active role in developing and revitalizing areas that are in dire need of a pick-me-up. In this sense, the theme of the festival expresses itself best as uplift and urban renewal. Until recently, many Kyotoites considered below Gojo Street to be beyond the pale. Next year Nakanishi talks of bringing the festival south of Kyoto Station and staging venues in Minami-ku. Later on this year, Reyboz and Nakanishi plan to bring the 15 main venues to Tokyo for an experimental run. Tokyographie must necessarily be essentially different from Kyotographie, but it is nonetheless gratifying to see the creative energy of Kyoto going up to the capital after the reverse being the case for so many years.