This memorable article by one of Kyoto Journal’s earliest regular contributors, Jonah Salz, on how Kyoto presents its living cultural heritage to visitors, appeared in our third issue, in 1987. Remarkably, it has hardly aged at all. Meanwhile, Jonah is still waiting – patiently – to see “dento bento” become a meme. Maybe this time…?

In foreign countries, what a respite! Here I am protected against stupidity, vulgarity vanity, worldliness, normality. The unknown language, of which I nonetheless grasp the respiration, the emotive aeration, in a word the pure significance, forms around me, as I move, a faint vertigo, sweeping me into its artificial emptiness… I live in the interstice…

—Roland Barthes, Empire of Signs

Leisure is the new religion, and tourism the modern pilgrimage. Each year, in growing numbers, middle-class tourist-pilgrims swarm the meccas of world civilization, holy guidebooks in hand, in search of a direct experience of foreign reality.

Tourists are children, brought ignorant before mysteries and marvels. They are innocents, trusting in licensed agents who shepherd them to exotic paradises. And tourists are kings, owners of all they survey, for the world’s parade of treasures seems to have been — and sometimes is — put together for their personal edification.

Tourists on a package tour or some other fixed itinerary, not willing to rough it or go native, and lacking linguistic competence, demand that the native culture be “translated,” made accessible in the preconceived terms of their own culture. Clifford Geertz notes that cultural performances — sports, rituals, dance, drama, and songs — present a wealth of condensed, symbolic information in a dramatic, experiential manner. They are “a story told about themselves to themselves,” transmitting ancient lore, technical skills, and group harmony.1 Tourists in search of a “quick fix” of exotic native culture, have naturally turned to “authentic” cultural performances. And these programs, designed and promoted specifically for outsiders, become “a story told about themselves to others,” mediated by barriers of time, language, and finance.

THE DENTO BENTO DEFINED

The dinner tray seems a picture of the most delicate order: it is a frame containing, against a dark background, various objects (bowls, boxes, saucers, chopsticks, tiny piles of food, a little gray ginger, a few shreds of orange vegetable, a background of brown sauce) and since these containers and these bits of food are slight but numerous, it might be said that these trays fulfill the definition of painting which, according to Pierra del Francesco, ‘is merely a demonstration of surfaces and bodies becoming ever smaller or larger according to their term.’

—Roland Barthes, Empire of Signs

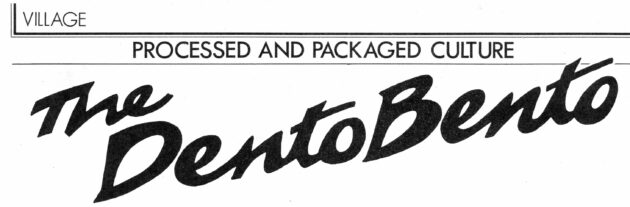

When native cultural performances and arts have proved intractable to external manipulation — too distant, obscure, or violent; amateurish, vulgar, or disappearing — they have been prodded to life before the tourist cameras. Folk crafts, ritual songs and dances, religious ceremonies and festivals, even whole villages have been “packaged” for domestic and international tourism. Producers carefully select and edit representative forms of culture to create a bite-sized, standard portion. Throughout the world, native culture is compressed, sliced and seasoned with a sauce bland enough for conservative tastes. Bangkok’s TTMland (Thailand-in-Miniature Land) features snakes, water buffaloes, and folk crafts in a “Thai village.” Haiti’s Mariani Voodoo offers ritual possession in a nightclub setting. In Bali, mask dances, gamelan music, and rituals are performed in hotels and bars. The list is long and lengthening. The Japanese seem to be particularly adept at telescoping time and space, genre and context, and compressing widely different arts and crafts into a single delectable package. I call this specially processed Japanese tourist package a “dento bento,” or “tradition lunchbox.” The bento is a portable, compartmentalized box containing a complete meal, often incorporating seasonal delicacies. The bento’s miniaturization process is one of symbolic condensation: each morsel is representative of a constellation of images. A single tempura shrimp sighs of the sea and autumn. A tiny ear of sweet corn evokes fertile valleys. Each unit is carefully framed within a higher order of harmonized color, taste, and nutrition in the self-contained meal. The time-honored bento flourishes today in the tightly scheduled Japanese workplace (itself a kind of self-contained bento box!).

Dento means “tradition.” A packaged culture show may be called a “dento bento,” because of the function it serves for the hurried tourist. Taken out of original social, religious, and political contexts, traditional culture is cut and dried, artificially sweetened and colored. The resulting pellets are then strung together as polished, coherent, light, self-contained tourist fare. Like international chain hotels, dento bento have less in common with their surroundings than with each other: a hotel show of Balinese dance may not be so different from a Moscow tourist performance of central Asian folk dance.

INSIDER’S BENTOS

Japan’s domestic market for tourism has had centuries to develop. Pilgrimages to Shikoku or Ise were often chance-of-a-lifetime occasions for travel and riotous revelry. The island nation is comprised of carefully delimited districts, each with its own (intentionally?) particular dialect, festivals, crafts, and foods. With prosperity, information gluts and mass transportation, packaged tours for domestic tourists to every hot-spring nook and quaint cranny have proliferated. And for those with less time or inclination, dento bento collapse whole cultures to daytrip size: Edo Mura in Tokyo and Meiji Mura in Nagoya; preserved and pickled towns like Takayama and Arashiyama and Kurashiki. Even centuries-old festivals are feeling the standardizing pressure of mass tourism: the Japan Travel Bureau offers a “four days, four festivals” package to Tohoku in August to see the four great festivals there. Other JTB packages shuttle tourists from Tokyo and Osaka to the culturally rich backwaters of Yamaguchi, Sado Island and Okinawa, on itineraries featuring exclusive two-hour performance smorgasbords.

Naturally Kyoto, cultural center and arbiter of tradition, is a master of packaging. The quaint yet wily shopkeepers and priests know just how to appeal to both the hometown snobs and visiting hicks. Whether the cherished dream of an elderly couple, the well-planned field trip of a junior high class, or the casual weekend of a college couple, a trip to Kyoto is a kind of “return to roots” for post-war society. The temples, gardens, geisha, and unique dialect make Kyoto a supreme deja vu, authenticating the “ancient capital” image that is a leitmotif of the nation’s education, literature and press. Kyoto is, and tries to remain, the Promised Land.

A good example of an insider dento bento occurred at Kyoto Kaikan last February. The Traditional Folk Entertainment Festival was co-sponsored by the Kyoto City Tourism Office, as part of a Winter Campaign to attract new tourists in the off season and perhaps to offset the temple closures caused by a tax dispute. It was an odd grab bag: comic kyogen tripped on the heels of romantic Hanagasa folksongs; oiran courtesans followed temple priests; a carpenter’s ritual preceded a street parade. Each group of performers, comprised of local community members responsible for the annual events, seemed delighted to present their proud traditions to a wider public of outsiders, and before their peers. This two-hour program succeeded in providing an amusing and authentic package of traditional ceremonies, and its folk charm derived from its very lack of polish.

GION CORNER: KING OF THE BENTO

A very different audience and aesthetic is at work in the king of the dento bento, Kyoto’s Gion Corner. Here authentic masters and professional production have combined to create one of the world’s longest-running shows. Since 1962, [as of 1987] nearly a million tourists, mostly foreign, have attended the hour-long presentation of seven traditional arts, offered twice nightly from March through November.

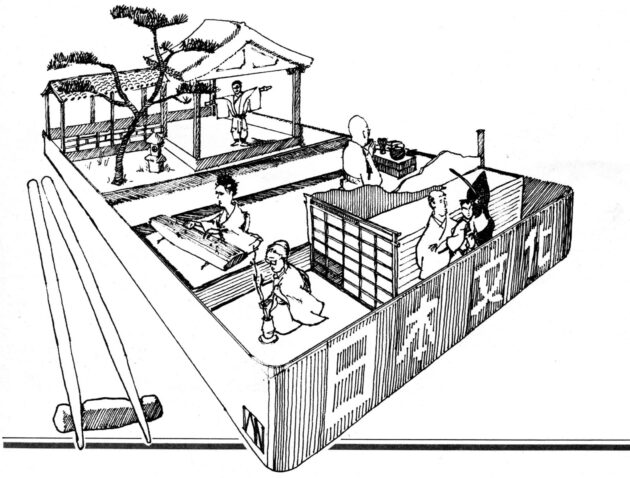

Even before the 1964 Olympics, Japan began receiving foreign tourists in significant numbers. Visitors to Kyoto had a full schedule of gardens, temples, and museums during the day, but little to amuse themselves with at night. The Kyoto City Tourist Office and the Kyoto Visitor’s Club (affliliated with Gion’s Kaburenjo Theatre), decided to put together a show for foreigners offering the best of Japanese traditional culture. The plan looked good on paper, but it required many compromises. First, it meant finding adepts of tea, flower arranging, koto, kyomai dance, bugaku (7th-century court dance), kyogen, and bunraku puppetry who were willing and able to perform nightly for an entire season. Next, it meant selecting pieces requiring little background knowledge: the familiar “Sakura” on koto, the slapstick kyogen “Tied to a Stick” (“Bo Shibari”), and a flashy bell-ringing scene from “Datemusume- Koi-No-Higanoko” performed by a lone bunraku doll. Finally, it meant arranging a program of these arts to fit a typical tourist’s schedule: each was chopped to 5-10 minutes, so that the whole show would take under an hour.

The show was an immediate success. Although there have been times when only one customer turned up (and the show went on!), there have also been sellouts. The only major change in 25 years was the replacement of the Hagoromo Noh solo by livelier kyogen, in 1965. Gion Corner’s unequaled record stems from its attention to detail, and its absolutely ruthless treatment of custom and tradition. The bento is concocted from proven ingredients: music, song, colorful costumes and quaintness. The whole show is packaged beautifully: in the heart of Gion, surrounded by teahouses, next door to the splendid Kaburenjo Theatre. Carpets, curtains and chandeliers provide a taste of Western elegance (quaintly tacky), while smooth continuity gives a rich gloss of professionalism to an otherwise disparate program. Each element of the performance—solo bunraku, edited kyogen, or staged flower arranging — is elevated to the same level of “traditional art” in the lengthy program notes.

Each act follows in swift succession, with no pause for reloading of cameras. Two audience members finish their tea and sweetcakes as the curtain rises to the strains of koto; as these die away, flower arranging begins. The entire traditional palette is watered down and souped up for the tourist palate. The result: a light souffle, delightful and enlightening, a show you must see, but only once. In the lobby, souvenir postcards and slides confirm the authenticity of the event. Some show the same performers — hair a little blacker and fuller — 10 years earlier.

AUTHENTIC SYNTHETIC

The traditional Japanese arts theatre situated close to Gion area, the home of Maiko (Kyoto’s geisha girls). The theatre was established to preserve the nation’s traditional arts and present them altogether for visitors. You can enjoy Japanese culture and the true spirit of Kyoto thoroughly.

—JTB Brochure

Gion Corner’s distinctive quality is its inherent, and perceived, authenticity. These are not sleazy, third-rate artists prostituting themselves to the low standards of ignorant tourists. All the Gion performers are masters, or are sanctioned by masters —trained and licensed by respected schools desirous of retaining their prestige. The maiko finish their first-show kyomai, hop across the street to a teahouse appointment, then return for the second show. Some autumns find the kyogen actors hurrying from Kobe, Osaka or Kyoto Noh stage performances, to Gion Corner for a “nightcap.”

No one is in it for the money—although 25 years ago, the tourist dollars enabled some borderline professionals to continue their careers. Even at ¥2,000 per ticket, full houses cannot generate much income, most of which goes to iemoto (heads of schools) for costume maintenance and administration. For apprentices in tea or kyogen, it is a good opportunity to perform outside the infrequent (and expensive) traditional recitals. But there is a real sense on the part of all of the subsidizers — the City (even when it was in the red), the iemoto and the performers — that presenting these arts to foreigners is intrinsically of benefit to Gion, Kyoto, Japan and the arts. Then, too, some performers enjoy the lively reactions of the foreigners, as opposed to the typical, staid solemnity of Japanese audiences.2

Some arts adapt more readily than others to the Gion Corner format. Kyogen, accustomed to slipping and sliding in various settings, comes off well enough in abridgment. Koto and bugaku have large repertoires that are easily shortened. But the private, solemn ceremony of tea seems strangely awry as two giggly foreigners perch on stools while a gaggle of photographers intrude over their shoulders. And flower arranging, normally a domestic art, becomes a showy performance. The package is the message, the sole arbiter of tradition-ality: there is no mention in the lengthy program notes that this is not how tea ceremony or flower arranging are normally done, nor that a bunraku master never performs alone, or to taped music; nor that the kyogen has been chopped by two thirds.

Gion Corner continues to thrive, as its word-of-mouth reputation and longevity make it a tradition in its own right. It has even become part of a larger package. The Gion Night Combination Coupon offered by JTB starts with a “Tea Ceremony Party & Private Buddhist Room with zen gruel” at a Gion teahouse, progresses to Gion Corner, and wraps up the evening at the nearby Maharajah disco! The best (?) of old and new Kyoto in 3 hours!

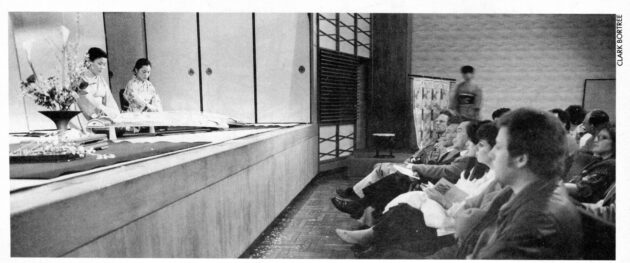

Gion Corner even has competition: the Samurai Nippon Show at the Shogun Theater (inside Fushimi Momoyama Castle), where the usual arts are joined by a demonstration of wedding kimono, karate, “ninja” and even harakiri (ritual suicide). The show climaxes with “A world champion of watermelon cutting on customer’s stomach.” A stern samurai stares from the back of the brochure: “Mr. Entertainer, Joe Okada” of Joe Okada Travel Service.

Conceived for foreigners, Gion Corner at first was off-limits to locals. It was felt that Japanese tourists, clacking out of ryo-kan in geta sandals and yukata robes, might upset foreign guests with their rude behavior. This has changed, and now 10 to 20% of the total attendance is Japanese. A few years ago, the Kyoto City Tourist Office inaugurated a special Gion Corner for Japanese tourists in the slow season of January and February. The once-nightly show was advertised in Japanese only, with reduced ticket prices, and replaced the familiar koto and flower arranging with more esoteric imayo ballad singing and ichigenkin samisen. The show was also a success, and continues annually.

There is a special, double authentification process occurring when both foreigners and Japanese attend Gion Corner. The foreigners, perhaps suspicious when they enter the airport-lounge decor, are reassured when they see Japanese tourists consulting their programs, taking pictures, and murmuring favorably. Foreigners have come to the Real McCoy; Japanese act as symbolic verifiers, like trucker’s cafes where those who should know go to eat. And for the Japanese, there is a double reaction: pride that their own, traditional culture can so please an international audience; and shame that they themselves are so ignorant of their own culture.

A MOVABLE FEAST

As Japan has come to economic and cultural prominence in the West in the past two decades, a growing audience of curious Westerners have had numerous occasions to partake in exported dento bento. Producers may be promoting a face-lift for the soured image of “Japan Inc.” or just making a quick buck off the Japanese boom. Japanese arts and crafts, atmosphere and spirit, are condensed and presented in a colorful and pleasant way — you can visit the now-scrutable Orient without leaving your own backyard. Sushi bars in New York’s East Village feature kimonoed geisha waitresses and stone-faced samurai chefs, paper lanterns, neon and shakuhachi music. “Japan Weeks” and “Sakura Festivals” throughout the world give an opportunity for expatriate Japanese and Japanophiles to drink sake, eat takoyaki, wear yukata, and enjoy folk dance and music. All this overlaps, of course, with the worldwide appetite for authentic atmosphere, ethnic color, and mini-extravaganzas. Even Japan can’t outdo Disney, whose EPCOT Center has a Japan “festival” section replete with Noh masks, teriyaki and folk crafts.

It seems clear that the dento bento can only go in one direction: up. By 1999 I foresee a Dento Bento Tower along the lines of the present Kyoto Handicraft Center. On each floor, a different traditional art or performance will be demonstrated: Noh, kabuki, pottery, even mochitsuki (pounding rice into New Year cakes). Smiling, multilingual guides will explain the nuances of the performances over headphones. Then all will head to the souvenir displays, to carry back some relic of this magic moment. ■

Author

Jonah Salz

Author's Bio

Jonah Salz has lived in Kyoto on and off since 1980, studying kyogen and intercultural theatre. He directs the Noho Theatre Group (1981-), co-founded Traditional Theatre Training (1984-), and is editor of A History of Japanese Theatre (2016). He teaches comparative theatre at Ryukoku University.

Credits

Graphic by Ian Perlman, another early regular contributor, who wrote mostly under a series of creative aliases…