August

It was August and I was standing at the study window, looking out onto the garden, when it hit me. “A fly,” I said. I couldn’t remember having seen one in months, since we had come to the city, and it would be many more months before I would see one again. Such a long time, in fact, that I began asking around where they had all gone, until someone finally told me: they had been exterminated in a sterilization program that kept them from breeding. This sounded extraordinary, although not inconceivable, and it was a while before I found out that it was only half true. The “sterile insect technique” had been applied in the 1970s to eradicate the melon fly and other pests in Okinawa, but there was a more straightforward explanation for the scarcity of the domestic species in downtown Tokyo: the city’s cleanliness and its inhabitants’ discipline. Except for certain parts of town and specific times of the day, you hardly notice any trash on the streets at all. It’s not that there isn’t any: a culture where packaging is so important — in every sense — produces a prodigious amount of garbage. But it is mainly “clean” rubbish: packaging is thrown away and again meticulously packaged, so it only becomes visible when crows tear the bags open in search of food. This is why, in Tokyo, people associate garbage with crows rather than flies.

Crows

Flies, like crows, are generally not very well-liked. They are diurnal, but associated with the night and darkness; they are spawned in the heady days of summer but are attracted to the stench of decay. They come and go along the road to the afterlife, swarming around the psychopomp. They are ominous creatures and in many cultures, equivocal emissaries. Their noisy, obstinate buzzing is like the crow’s irresponsible cawing. They drive us to distraction, irritate us until we slap at them and close the window, only to find that they’re still inside.

May

They’re unavoidable. They appear as far back as the Kojiki at a critical moment in the creation of the world when the light withdrew and darkness spread across the heavens, and “the evil deities’ voices were like swarms of mayflies, unleashing countless portentous calamities.” These ominous swarms also appear in the Psalms, but while biblical flies evoke deserts and hunger, those of Japan suggest the abundance and plenitude of summer which, according to the old calendar, used to begin in May. This precise temporal reference is typical of Japanese culture, and so too is the sensitivity of an ear that can hear the voice of demons in the loud buzzing of flies. At the same time, they are more inconsequential: barely an image, one that buzzes rather than devours.

Given the importance of silence in traditional Japanese culture and the attention paid to the voices of insects, I am hardly surprised that in modern Japanese the word urusai — “noisy, annoying, bothersome” — still can be found written with three characters whose literal meaning is “mayfly.”

Legs

Japanese literature probably has the largest insect collection of any country in the world. In a memorable chapter of Genji Monogatari, which Arthur Waley mysteriously left out of his translation, Prince Genji surreptitiously makes preparations for a private koto concert at his lover’s house, and orders the garden to be filled with crickets to provide the melancholy background music. Not far from there and around the same time, Sei Shonagon makes an aside in the passage on insects in The Pillow Book and notes that: “The fly should have been included in my list of hateful things; for such an odious creature does not belong with ordinary insects. It settles on everything, and even alights on one’s face with its sticky feet,” further complaining that children are still named after the fly.

Issa

It settles on everything. It’s an impertinent intruder. No one needs it and no one misses it. But one person did refrain from shooing it away. Among the hundreds of poems written by Japanese authors about flies and their vexed hunters, the most famous —there’s a whole book about its long genealogy and vast progeny — is without doubt the one written by Kobayashi Issa (1763–1827):

やれうつな蠅が手をすり足をする

yare utsuna hae ga te wo suri ashi wo suru

No, not that fly!

It wrings its hands,

its feet, imploringly.

Though the original does not rhyme, it does feature the alliteration suri/suru. This is the verb “to rub,” which also appears in one of Issa’s lesser-known poems that may be interpreted in Spanish — with a certain amount of poetic license perhaps, but without losing the literal meaning — as good-humored social comedy, since “dead fly” in Spanish is mosca muerta, whose figurative meaning is “hypocrite.”

縁の蠅手を摺るところ打たれけり

en no hae te wo suru tokoro utarekeri

On the veranda

the dead fly

rubbed its hands.

This is not to say that Issa was always such a Franciscan in his love of animals. At times, like anyone, he got fed up and lashed out — and, like anyone, it was in vain:

群蠅のモ逃げた背紀跡打皺手哉

mure-bae no nigeta ato utsu shiwade kana

The swarm of flies

flees and leaves me

with a wounded hand.

Like anyone, he was bothered by the persistent buzzing that almost seems to speak to us with the same incomprehensible levity with which men clamor for attention from the gods:

蠅寺や神の下らせ給あうとて

haedera ya kami no kudarase tomau tote

Flies in the temple

ask the gods

for this and that.

The original says haedera, which evokes Hasedera, the beautiful temple halfway between Kyoto and the Ise Shrine mentioned in innumerable books, but it’s an invented name: Temple of the Flies. A Buddhist temple for worshipping the Shinto gods, signaling the confusion of the times and the inconsequence of men. The poem is a short fable and the poet here is a moralist, one that Issa later regards ironically. Because of this, it doesn’t strike me as wrong to convert the Japanese invocation to Buddha, Namu Amida Butsu, into a Lord’s Prayer.

蠅一つ打ってばなむあみだ仏哉

hae hitotsu utteba namuamidabutsu kana

For every fly

that has been swatted,

a Lord’s Prayer.

Shiki

Aren’t prayers for fallen flies a bit of an exaggeration? How many flies could Kobayashi have really killed anyway? And for that matter, can you really kill a fly? Aren’t they all one and the same, reborn and breeding? This is what the founder of the modern haiku, Masaoka Shiki (1867–1902), seems to suggest, as he clearly shows his frustration in this poem:

秋の蠅

蠅たたきみな

破れたり

Autumn flies.

All flyswatters

Smashed to pieces.

On Meaning

How busily

they reel, toil, fly

tirelessly

light tiny flies

among the remains

like a heart

beating blindly.

≥

Author

Aurelio Asiain

Author's Bio

AURELIO ASIAIN is a well-known Mexican poet, editor and translator who arrived to Japan as a diplomat, decided to stay in Japan and moved to Kansai. (He wrote the last poem above, by the way.) His most recent books are Luna en la hierba, a bilingual commented anthology of classical waka and ¿Has visto al viento?, poetry. He is also a published photographer: aurelioasiain.blogspot.com

Credits

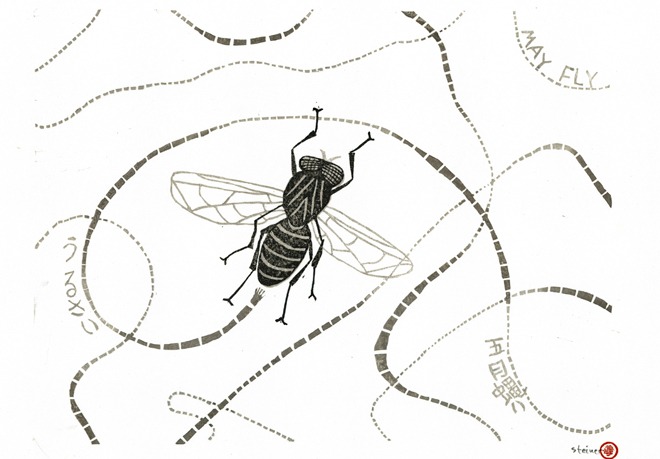

Artwork by Richard Steiner. Richard is a successful printmaker and teacher, as well as the founder/president of KIWA, the Kyoto International Woodprint Association. www.richard-steiner.net, www.kiwa.net