When the weather’s hot like this, I always think of the “Summer Moon” sequence from the linked-verse collection The Monkey’s Straw Raincoat.

“Smells of things

In the marketplace

The summer moon”

That’s a good verse. A precise expression of a very specific sensory experience. I always visualize a fishermen’s market. Others may picture Jinbôchô in Kanda or be reminded of the night stalls in Hatchôbori—it’s different for everyone, I suppose, but any scene that comes to mind will do. What’s amazing is how vividly the verse serves to bring back a summer night from your own past.

Raincoat is virtually a one-man show by Bonchô. Surely that’s overstating it, but it is undeniable that Bonchô has two or three real masterpieces in this collection. Smells of things / In the marketplace / The summer moon. If a man were to compose only three verses as outstanding as this in the course of his life, he might well go down in history as a master of haikai. There aren’t that many haiku that can be called masterpieces. If you take a good look at the “Summer Moon” sequence, you’ll see that most of the verses are a little strange.

“Smells of things

In the marketplace

The summer moon”

To this, Bashô attached the following:

“So hot! It’s so hot!

Voices at every gate”

Things have already gone awry. Bashô has stooped to a tedious explanation of the preceding verse. It’s superfluous. It’s as if someone were to cap his

“Ancient pond

A frog jumps in

The sound of water”

with:

“After the sound,

Silence”

Well, not quite as bad as that, but it’s the same sort of crime—a redundant appendage. Even the Master could blunder. For all his preaching to his disciples that in linking verses one mustn’t be overly obvious, that one should rely on the veiled intimations of omokage, the Great One himself still occasionally came out with disasters like this. This isn’t linking, it’s welding. Bonchô has knocked the Master right out of the ring, and he’s helpless to retaliate. So hot! It’s so hot! / Voices at every gate. We already know that from the previous verse. How utterly inept. Next comes Kyorai.

“Though the second weeding

Is still unfinished—

Ears on the rice”

It’s hard to suppress a snicker. Kyorai probably took great pains in squeezing out this verse. He was a staid, serious-minded, countrified fellow. Nothing foppish about him. But rustic people are apt to want to try their hands at being foppish. They aspire to adroitness, ingeniousness. Rustic poets should compose rustic poems. When they do, they come up with splendid verses, verses that not even the cleverest wits can touch.

“Biwa’s waters

Have visibly risen

Summer rains”

This is Kyorai at his best. As long as he sticks to this sort of solemn and sedate tone, he’s a truly fine poet. But when he gets clever and oddly contrived, one can scarcely bear to watch. It’s embarrassing. Kyorai, however, far from being aware of how pathetic his “clever” poems strike us, presents them with a triumphant flourish, which only makes it all the harder to look. The best we can say about this side of Kyorai is that it’s kind of endearing. Bashô, too, resigned himself and went ahead and loved Kyorai best of all his disciples. Though the second weeding / Is still unfinished— / Ears on the rice. It’s boring. There’s nothing of interest in this verse. It’s just plain dull. No doubt he struggled over it. You can almost hear him: “Though the second weeding . . . It wasn’t easy coming up with this first line, I’ll tell you. How do you like it, though? Rather a clever device, what? Is still unfinished— Yes, I had a hard time working out the phrasing here. It’s a delicate spot, you see. But I think this fits the bill quite nicely . . .” And so on. What response, aside from a wry smile, can we possibly have? The more I read it, the more embarrassed I get, somehow. Kyorai-san, I beg you, do stop trying to be clever.

“Tapping the ashes

From a dried sardine”

Bonchô follows up with this. Not bad. You can see the farmer woman standing there. There’s something affected about the verse, however. Something sardonic and condescending about it. Bashô comes next.

“This far down the road

Even money’s a stranger

Living in want”

It’s a little vague. I see this verse as the muttered complaint of the farmer woman. The normal interpretation goes something like: “People in the country live in such destitution that they’ve never even seen money.” In other words, it’s an outsider speaking, making an observation about poor countryfolk. But if that was the intention, it’s a hopelessly stupid verse. This far down the road becomes sheer sarcasm, and “they must be in want because they don’t have any money” is such simpleminded logic it’s virtually meaningless. It seems to me that This far down the road is a phrase that has a touch of dialect to it. It’s something a farmer would say. Tapping her sardine, the farmer woman is complaining in a somewhat self-deprecating way. No less a personage than Kôda Rohan suggests that This far down the road is to be taken in a literal, geographical sense, but I can’t help seeing it as a vague, ambiguous sort of phrase meaning “people in our situation” or “nowadays” or “at this point in our lives.” In any case, it’s not a good verse. It’s not clear if it’s subjective or objective. “The rain was pouring noisily down, but I wasn’t aware of it at all”—Bashô’s verse has something in common with moronic prose sentences of this sort. If the verse is meant to be objective, it’s hopelessly obvious. It has a bit more life to it if it’s meant to be a farmer woman muttering to herself, but then it’s too dependent on the previous verse. Disgusted, perhaps, at having been bested by Bonchô again, Bashô seems to have lost the will to go on. The Master was forever being selfish during linked-verse sessions. Sometimes he just gives up completely. Gets dispirited, I suppose. Unaware of this, however, waiting in the wings, devising his next feckless little contrivance, is Kyorai.

“Utterly incongruous

His long shortsword”

Fabulous. Now we have an absolute mess. Kyorai, no doubt, was delighted, inwardly congratulating himself, but it must have sent the others into shock. The lines just come out of nowhere, a fish in the desert. What to do now? Bashô and Bonchô both must have felt like throwing in the towel. Kyorai, thoroughly pleased with himself, would have been oblivious, however. After pulling weeds, he spins around and whips out a sword. One can only be astounded at the workings of a mind like this. He’s botched the whole business with two lines. It’s sensational, unprecedented. Because of this one verse, the next thirty don’t have a chance. There’s no way to follow up on it. Kyorai alone is sitting there bursting with enthusiasm. But it’s Bashô’s fault, really. It’s because of that ambiguous, mystifying verse of his that Kyorai leaped in with such an outlandish response. One even wonders if Bashô wasn’t just being mean. Teasing poor Kyorai, if not flat-out making fun of him. This far down the road / Even money’s a stranger / Living in want. Handed this obtuse verse, Kyorai-sensei was thoroughly flustered, no doubt, but merely gave a grave nod and, BOOM: Utterly incongruous / His long shortsword. It seems to me that you can read the psychology of both of them in this exchange. At any rate, this sword business made a complete shambles of everything. Bonchô, stifling a fit of the giggles, pens the next link.

“Into the thicket

Scared by a frog

Twilight”

Clearly an inferior verse. Some say that there’s not a single poor verse by Bonchô in Raincoat, that they’re all outstanding, but that’s certainly not the case. Most of his poems here, in fact, are inferior ones. If there were as many superior verses as those people say, Bashô would have become Bonchô‘s disciple. It’s doubtful whether Bashô himself has ten truly great verses. Composing haiku is like firing pottery—they rarely come out as you want them to. After a hundred failures, you might, if you’re lucky, have one success. Most people, I dare say, never even come up with one. After all, you have only seventeen syllables to work with. Into the thicket / Scared by a frog / Twilight. I wouldn’t say it’s vulgar, but it’s definitely cheap. He’s just playing along. It’s a stopgap.

“In search of butterburr shoots

Her lantern goes out with a shiver”

Bashô follows with this. He, too, is just going along for the ride. Anything to get away from Kyorai’s sword. It was either something of this sort or nothing at all. That long shortsword was just too alarming. The lantern goes out with a shiver. That’s a descriptive passage worthy of Bashô. He quietly snuffs out the intrusive weapon. Having finally managed to pack the sword away, he breathes a short sigh of relief. Then Kyorai-sensei drops his third bomb.

“She entered the Way

At a time when the cherries

Were still in bud”

Splendid. Impeccable verse. But it’s not the least bit interesting.

The other day a certain serious, middle-aged gentleman showed me some haiku he’d written, and among them was one that went: The pure white moon / A mirror for / Mischievous minds. It bore the title “The Heart of Buddhism.” Now that, no matter how you look at it, is a masterpiece. I was unable even to express an opinion. When you run across a truly superior verse, you can only stand in awe.

Bonchô’s mood, understandably enough, is turning sour now. He inscribes the next lines with a severe, cold countenance.

“Nanao in Noto

A grim life in winter”

He completely ignores Kyorai. Slams the door in his face. He’s a bit angry, and it’s a hard-edged, rigid verse. Adamantine. No melody; pure rhetoric.

“Grown so old

That it’s come to this

Sucking on fishbones”

This is what Bashô comes back with. Things are really getting dark now. There’s an air of gloom hanging over the company. Bashô, especially, is in a sour mood. He’s becoming downright captious. The fault, mind you, is clearly with She entered the Way. Good old Kyorai has blown it again.

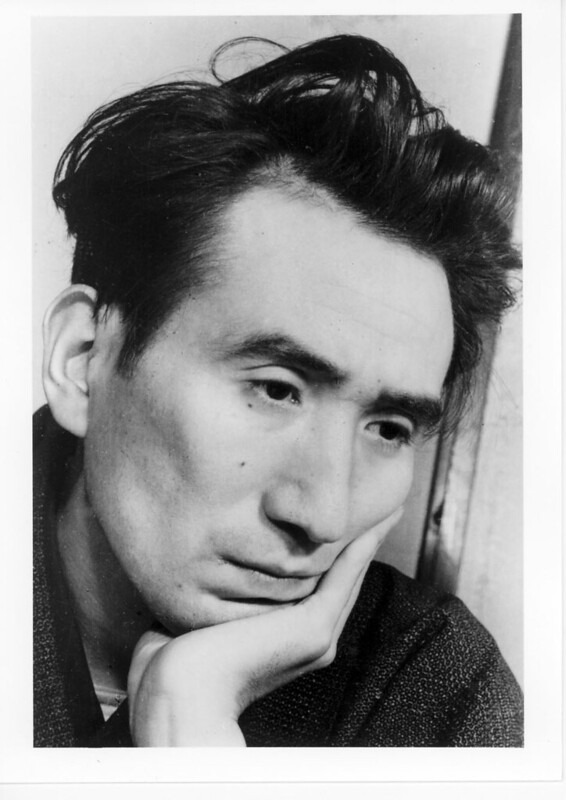

Dazai Osamu

Well, “Summer Moon” continues for another twenty-five verses, but most of them, sure enough, are inferior. I’ve written just the number of pages I promised to write, so I’m not going to go on about the remaining links. Looking back at what I’ve written, I have to admit that I’ve been outrageously impudent. Bashô, Bonchô, and Kyorai have all gone down in history as great masters of haiku. To amuse oneself on a summer night by insulting and teasing them is no small crime. Suddenly gripped with panicky repentance, I’ve decided to entitle this essay “Tengu.”

Overcome by the summer heat, the writer has transformed into a devilish, red-faced goblin. Forgive him.

Author

Osamu Dazai, trans. Ralph McCarthy

Author's Bio

Osamu Dazai was a Japanese author who is considered one of the foremost fiction writers of 20th-century Japan. Ralph McCarthy is the translator of two collections of stories by Osamu Dazai—Self Portraits and Blue Bamboo—as well as the upcoming Fairy-Tale Book of Dazai Osamu.

Credits

Images sourced from Flickr.