Page Contents

[C]arrying steaming cups of homemade chai, Jack and I descend the kitchen stairs of his ranch style house toward the adjacent studio. Inside, morning light filters down from the gable skylights, settling on tubes of oil paint, brushes and a glass palette positioned on one of the worktables. Nearby is the long, red-lacquered desk Jack recently built for his computer and mini recording studio. Two of the walls in his spacious hideout are wood-paneled, and two are white. All are hung with Jack’s paintings, wall sculptures, bone carvings and Asian memorabilia. On a second worktable, near a comfy old sofa, stands the vase with fresh flowers that Eiko, Jack’s wife, always arranges with great care.

Jack lights a stick of incense, and the mild smoke mixes with the studio’s ambient aroma of linseed oil. He turns on the banks of lights, and then the stereo. To the lilting voice of a bamboo flute, we settle into chairs to sip our sweet Indian tea.

With a self-effacing smile, Jack holds up a tiny device he’s invented to map the inner contours of a bansuri flute, the North Indian instrument he began to play some five years ago. He makes his own flutes from a special bamboo that he grows. Precise readings from his new gadget let Jack sand out the bamboo’s narrowing ends to just the size that produces exquisite timbre. Echoes of his earlier years as an engineer — but that’s a story for later.

How many times have I joined Jack Madson here at his home by this forested river gorge — how many pilgrimages to Felton, California since Jack left Kyoto two decades ago? I’ve lost count, but on every occasion, atop the discovery of new directions in his paintings, I’ve found him absorbed in fresh endeavors: Stained glass. Woodwork. Printmaking. Ceramics. Photography. Vipassana meditation. And always some form of music. Now in his seventy-ninth year, Jack Madson is as ever a man in whom life is superabundant.

While he lived in Kyoto from 1962 to 1986, Jack was the emblematic Western artist in Asia. He came because he had to, stayed far longer than planned, punctured his preconceptions and in return savored the nectar of more than one foreign culture, principally those of Japan and India. Like many expatriate artists who settle in Japan’s old capital, Jack found it conducive to a hermit-like part of his nature. “You could be practically invisible,” he once explained, “and you didn’t have to obey all the mores and folkways. You could be freer in Kyoto than in this land of freedom here. I made use of that to develop myself, a very important reason why I stayed as long as I did.”

As has always been our custom, we slowly go through the year’s harvest of paintings, placing each on the familiar easel that Jack himself constructed, giving me plenty of time to report the images I see within. His art is so adept at riding the edges of associations, so probing of the viewer’s own imagination, that I tend to speak in unfinished sentences, barely naming what seems like one recognizable organic form before it melts away and another seems to congeal.

Jack delights in hearing what people see in his work, while he will never, ever reveal what he sees. Methods, techniques, materials — all these are an eagerly opened book; aesthetic and spiritual aims as well. But contents he’ll only discuss when the painting is representational.

At one point, while Jack’s switching paintings, my eye is drawn to a picture hanging nearby. Its imagery, suggesting birds in flight, is strikingly similar to a Madson etching I have in my home in Japan. “Yep,” Jack confirms, “Same title: ‘Migration.’ That’s the painting your print was based on. I painted it years ago, back in Japan.”

A light comes into his eyes. “That word ‘migration’ — it really turns me on. A book I’m reading now is all about bird migrations. Did you know that tiny hummingbirds that weigh about the same as a penny will fly across the whole Gulf of Mexico, five hundred miles in a single flight?

“And the arctic tern, it migrates from the North Pole to the South Pole and back every year. Ten thousand miles each way; there’s no farther distance on the whole planet! An arctic tern! It’s not very big. These birds have ways of knowing where food is. The ones that have what they need will stay where they are and not migrate. There’s so much to learn from birds. When I was a child they were my first absorbing fascination in life.”

Jack’s migration to Japan, and from there six sojourns in India. The traveling back and forth between genres, forays into new mediums; the countless migrations within the cosmos of every painting, and well before that, the leap from industry to fine art. The impetus which propels a flock of wildfowl across an expanse of the earth has time and again driven Jack and his manifold genius to where his soul’s nourishment could be found.

In Tools, a Beginning

[M]ilwaukee, Wisconsin, the late 1930s. A father figure and friend of the Madson family shows ten-year-old Jack how to handle tools, explains electrical circuits, and regales him with tales of deep sea diving. “He spent a lot of time with me, and would even tell me cock and bull stories of fighting sharks in Lake Michigan,” Jack fondly recalls. “I remember lugging a book home from the library numerous times, Deep Diving and Submarine Operations. I just lived in this book for, God, a couple of years. At age thirteen I decided to make a helmet to go underwater. It seemed like the greatest thing to do. I started with a five-gallon ice cream pail, cut an opening and made a design, then built it and tested it out at the local big swimming pool.” A photograph in the Milwaukee Journal. The caption: ‘Young Diver Finds Way to Escape Heat Wave.’

“But I hadn’t studied hard enough, because the helmet wouldn’t go under, it was too buoyant.” Then Jack and his buddies tie a hefty rock to the top, and while the two boys send him air with a pair of tire pumps Jack submerges and walks around on the bottom. “It was the most fantastic thing I could ever imagine. We took turns.”

The next year, as the US enters World War II, Jack begins building another helmet with a full diving suit. “And we had this company in Milwaukee manufacturing diving equipment for the US Navy. They built more underwater gear than all the other firms in the world put together. So at fifteen I went there and asked for any kind of a job. I just wanted to be around all this stuff.” Turned away for being too young, Jack comes back on his sixteenth birthday and is hired full-time. Swiftly he masters machine shop skills, running lathes, drill presses, saws and mills. “And I brought in my three-quarters finished helmet and worked on it during my lunch breaks, pilfering parts from the shop and otherwise keeping it hidden. One day the company president, a tall guy, square shoulders, comes in and spots my helmet. I was terrified — thought I’d be fired.” Instead, awed by Jack’s ingenuity, the chief assigns him to work in the company’s experimental lab. “To my amazement, I became his right hand man. And I learned so much working there. But then, with the war on, at seventeen I had to go into the service. A good word from my boss put me into the Navy’s deep-sea diving school — straight from boot camp, unprecedented. A few salty guys there resented me. They’d worked long and hard to get in.” Now the living seabed becomes Jack’s workshop as he learns the techniques of underwater construction and demolition. Some years later, his first oil painting: a helmeted diver deep in a lush, undersea grotto.

After the Navy, Jack works on a Florida schooner, marries young, then joins a paper-converting machinery firm in Milwaukee. Apprenticing on the factory floor he’s enthralled by the oft-reconfigured, 40-foot line of convoluted machinery. Once more his talents emerge and in time he finds himself, white shirt and tie, ensconced at his own drawing board in the engineering room. Meanwhile, sons Craig and Mark are born. In his spare time Jack takes up darkroom photography. He also redesigns a sports car, re-shaping its side panels with parabolic curves.

In the mid-1950s, approaching thirty and still very much in love, Jack follows a restless, migratory urge and enrolls in night classes in drawing and painting at the local art institute. There he comes under the wing of Robert Von Neumann, “one of the more important persons that gave shape and direction to my life.” The Berlin-born artist’s fine etchings and lithos of fishermen at work introduce Madson firsthand to “the idiom of flow and movement in a composition, aside from its subject” — but equally consequential, “Vonnie” and the other artist-instructors Jack meets in the evenings have “values that I aspired to, like the understated courage to pursue real freedom, and the patience, curiosity and enthusiasm that I find crucial.

“The contrast between my associates as an engineer and these artists was just astonishing to me. I became like a student of human nature. The values of those successful people at work, at cocktail parties — I shouldn’t knock it, it’s good for folks to have money, but somehow I never had the same attitude. My teachers at night, these artists, I felt, ‘I want to be like those guys.’”

Resolve

[J]ack leaves the engineering firm, and in two years on scholarship clinches a BA at Milwaukee’s Layton School of Art. Intrigued and initially puzzled by the abstract expressionist works of Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock, he gradually wings his way towards a non-figurative mode all his own. Awards and recognition ensue. Wife Chris, a registered nurse, wholeheartedly backs his new direction, holding down the fort as Jack goes off to Michigan for a year of funded MA studies at the renowned Cranbrook Academy of Art. More honors accrue, then a teaching post at Cranbrook. The whole Madson clan moves to Bloomfield Hills — three more happy, productive years. Yet all along, Jack senses something is wanting.

“Down inside me for years I’d felt that I needed to get away from everything I’d been raised in. I’m not complaining, my life was wonderful. But I had to see how other cultures lived: their arts, foods, clothing. And something underlying all that. My original goal had been India, the furthest I could get from my background. I was so curious about the world, and knew so little. I wanted to live in a country with a strong, encompassing tradition, which we don’t have in the US. I’d met some Japanese students in college, and gradually my practical side made me realize that if I went to Japan I could make a good living, enjoy its old traditions, arts and ways of looking at the world, and also have the new things I needed, like libraries and museums.”

With the blessing of his wife, who returned with their sons to Milwaukee, Jack spread his wings in 1962 for a planned year abroad. Crossing the Pacific Ocean in steerage, he learned Japanese folk songs from farmers and students, who also taught him the game called go, and he ate endless bowls of soba and ramen. When his ship docked in Yokohama on a Friday in June, he traveled straight to Kyoto, where his first Japanese habitat awaited discovery: a good-sized outbuilding within the peaceful grounds of Kokushoji Temple in Gobancho, once a laborers’ red-light district. Add a wooden partition or two and there would be plenty of room for both home and studio.

His eyes were aglow with new sights. Most surprising at first was Kyoto’s wooden architecture, for photos in books had not conveyed the wonder of “enormous tiled roofs supported by little poles.” Roving on foot or by motorcycle in and around the ancient capital, Jack often stopped to quietly sit on doorsteps or windowsills and observe craftsmen at work. “The carpenters and woodworkers I watched were beyond count. Stonemasons, metalsmiths, tailors, gardeners, tatami makers — all became teachers. Once, along the Japan Sea coast, I happened upon a maker of traditional paper umbrellas. With all the appropriate bowing and gestures he showed me to where I might sit against a post and spend an hour watching him shaving sticks of bamboo, then cutting the paper he’d later treat with a waterproofing oil. What was vital was to see firsthand the tools and brushes, how they’re held and manipulated and, of equal importance, the jigs, templates, clamps and one-of-a-kind tools needed for very specific uses, whatever the particular craft may be.

“The patience of the Japanese! The solitary craftsmen never looked at a clock. If you want to make something fine or beautiful, you shouldn’t have a clock in the room. Whatever it takes to make it right, that’s what you do, and don’t think about any other practical concerns. This was quite a difference from what I’d grown up with. And it would be easy to overlook the tempo, the pace, the calmness and attention with which these craftspeople worked. Fine artists were like this as well. I make no excuses for Abstract Expressionism, but some of it was ‘splash and hope.’ What I came to see in Japanese painting, in woodblock prints and all the other arts was a deep sense of caring, and always the best possible solution to the problem of what they’re trying to express or show. Nothing’s done haphazardly. This makes it deeply human. This finesse and excellence appealed to me strongly, and I tried to transpose that into abstract art, which can easily go off the wild end.”

Reciprocation

[J]ack does not paint from models, sketches, photographs or objects of any sort, depending instead on visual memories and inner fantasies born from years of study and closely observed experience. At the outset there is no preconceived image or goal. “I choose two or three colors I want to work with and decide between horizontal and vertical.” Then he begins with charcoal — drawing and smudging, erasing, and gradually introducing color. “Once there is enough division of space and hints of motion, the work itself becomes a participant in its own completion, even asking for erasures. The intent is to reach a state in which the painting takes on an identity of its own, one that is not dependent on, or distracted by, anything outside itself.”

Yet these organisms of light are anything but hermetic. Their innate structure — an enigmatic fusion of movement, form and color which Jack calls the “matrix” — somehow empowers them to conjure up and illumine visions unique to each viewer. The effect is inescapable when seen at full scale. In essence, Madson has built a middle ground between opposite genres — a fruitfully paradoxical zone that is neither representational nor purely abstract.

“He’s a magician who works with colors and shapes,” Eiko says as she joins us, bringing a tray of smoked oysters and a tokkuri filled with saké. Lifting my cup, I know at once who made it. What is style, after all, but the visual scent of character? And Jack is an artist who can intuit novel potential in such a diverse array of materials, even in found objects.

One day while riding his motorcycle on the road from Kyoto to Takao, Jack found a Japanese tansu lying in a gutter. Once a graceful handcrafted chest, it was “bleached from sun and rain, so abandoned and so unloved. Missing some drawers and panels, rusty metalwork. Hopeless, I thought, and drove on.” But the tansu would reappear in his mind “in a rueful way.”

Finally bringing the chest home, thinking to salvage its hardware, Jack eventually gave it “a good stiff brushing with soap and water,” and step by step, with no long-range plan or expectation, he watched the tansu begin to come alive. Some of the hardware needed for its restoration he found in his box of “valuable junk.” But for the missing large upper panel he sketched an original design, hammering out from scratch perfectly suited handles, hinges and metal fittings, and forging its signature pair of black crescent moons from iron he cut from an old Chinese wok.

One treasure that even Jack could not repair was his marriage to Chris, under strain and now cleaved by the very jubilation he’d found in Japan. Twelve months in Kyoto would prove impossibly short. He was in full artistic flower, and the groundwork was being laid for solo exhibitions.

So he made an agonizing choice and paid his share of the price. For a long time afterward, whenever the topic was raised or even approached, a shadow would darken Jack’s face. Perhaps he has healed now, if with a scar, for both he and Eiko, who met each other in early middle age, are close with Jack’s former wife. A major blessing of his return to America is the four grandchildren he has watched grow up, who come to Felton during summer vacations. While Jack lived in Japan, his two sons also made lengthy visits; the eldest, Craig, met his own wife in Kyoto. And so it goes that two of Jack’s grandchildren have a Japanese mother.

The Hermitage Salon

[F]our years into his stay in Japan, with solo shows in Kyoto and Tokyo well received, Jack found a humble, two-story traditional house in northwest Kyoto, on the edge of downtown, and set about turning the dust-heap into a marvel.

“The landlady said, ‘Do anything you want. Just don’t ask me for any money!’” In the kitchen, eyeing an old, uncared-for well next to the sink, Jack decided to find a rope and pulley and a pair of traditional buckets, then fashioned a fine bamboo cover. “At night you could lie in bed and listen to drops of water dripping down into the well. It was rhythmical, never the same music twice.” He designed and built a long kitchen cupboard, its door panels a brilliant relief stained in three colors evoking New Guinea, and for the nearby tatami living room made a low table, lacquered in red and inlaid in spots with antique coins and small figurines of silver. The sliding doors in his house soon displayed bold new paintings: dynamic, abstract fusuma-e.

In the small back garden he began by building a new earthen wall, patiently studying a time-tested Japanese method that calls for three different layers. He prepared the fallow ground to once again grow moss and then planted leafy, bamboo-like nanten. Inspired by temple gardens nearby, he carried home stones from the Kamo River and stacked them with care to make a stone lantern.

Filling his Kyoto house with elegant Japanese tansu, ceramics and art, Jack created an ideal space to display his own paintings, and into this home over the next twenty years would flow a steadily growing community of friends, neighbors and students attracted to the man from Milwaukee who, while certainly no extrovert, was unusually sensitive to a wide variety of characters and talents. Over time the house of the hermit became a kind of salon. “Dropping by Jack’s,” a painter friend recalls, “you never could guess who might already be there. His red table was like a hub.”

“One day,” Jack recollects, “just a couple of months after I’d moved in, my landlady came to pick up the rent, and she said to me, ‘This house has never looked so Japanese!’”

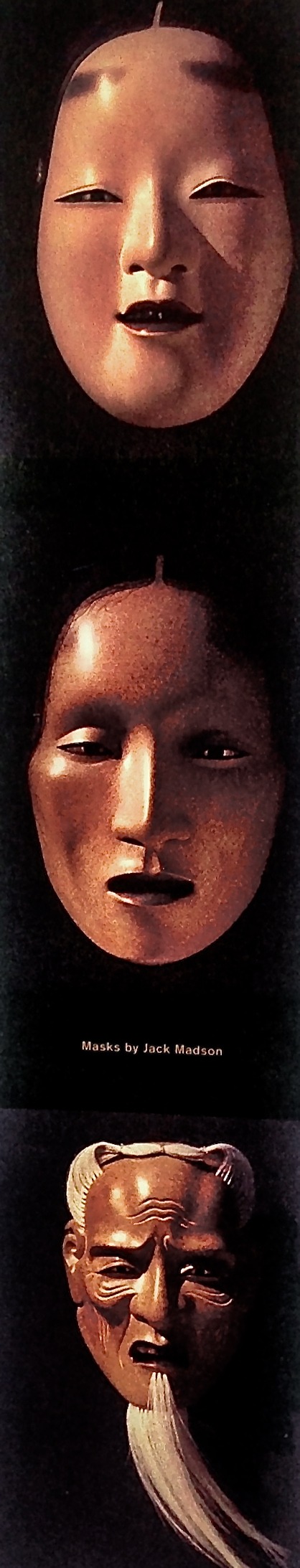

Masters of Masks

[N]evertheless, unlike many expat artists in Japan, Jack was averse to finding a master to study an established fine art such as woodblock printing. “From early childhood I’ve had this thing about self-sufficiency and independence, so I naturally shied away from practicing arts I found others doing. Besides, I was looking for things that would strike me personally. I like all the Japanese arts, and I went to a lot of exhibitions; whenever a show of carved masks was held I’d go.” One summer day in 1974 — a dozen Kyoto years behind him, a dozen more to come — Jack attended an exhibition of Noh mask artist Kitazawa Nyoi, a living national treasure.

“This master changed my whole picture. His masks were just astounding. I was really moved, and I thought, ‘If I could study with this guy I would do it.’” A friend introduced him, “and I worked with Kitazawa-sensei incessantly, with total devotion to this subject, for nearly eight months. I carved six masks. Yet even just watching this master carving was an education in itself. It’s hard to explain how a series of skillful cuts can reveal the underlying plan or vision. This all comes with great dedication and experience, plus something mysterious and only partially conceived by the artist. I once told Kitazawa that I thought a mask of his looked like him. He agreed and said that if I kept carving, some resemblance to myself could be expected in mine as well. It’s not a calculation on the artist’s part, but a manifestation from the subconscious.”

“This master changed my whole picture. His masks were just astounding. I was really moved, and I thought, ‘If I could study with this guy I would do it.’” A friend introduced him, “and I worked with Kitazawa-sensei incessantly, with total devotion to this subject, for nearly eight months. I carved six masks. Yet even just watching this master carving was an education in itself. It’s hard to explain how a series of skillful cuts can reveal the underlying plan or vision. This all comes with great dedication and experience, plus something mysterious and only partially conceived by the artist. I once told Kitazawa that I thought a mask of his looked like him. He agreed and said that if I kept carving, some resemblance to myself could be expected in mine as well. It’s not a calculation on the artist’s part, but a manifestation from the subconscious.”

Once he’d learned the fundamentals Jack began designing and making his own mask at home, from scratch with an oil clay model. “You get this clay, which doesn’t dry, to the shape that you want and then make stiff paper templates, horizontal and vertical, to transfer the shapes to wood. In the studio I didn’t tell the master what I was doing or ask any questions about it. And when I got that mask finished, near the end of our association, I took it in to show him.” Kitazawa was so impressed that he gave Jack a silk embroidered bag for the mask, an honor reserved for “genuine” work. “Then he told me, ‘In Japan you could now make a living carving Noh masks.’

“But there’s too much outside responsibility. In the pantheon of Noh plays there are lots of princes and people who, to me, just don’t have interesting faces. I like devils, women and old people. That’s about it. So, before long I went back to painting and on to other arts, but what a wonderful experience! During this time, when riding on buses and trains, my powers of observation of people’s faces were just enormous. I was looking at every little detail around the corner of the nose — is that sharp or round? Does this go up or sideways? Just to be in that state of mind, so focused, that’s what guides me through my whole life: finding things that make me feel great to be alive. These are self-revelatory, too. You find yourself thinking and observing in ways that you hadn’t known were in you. Kitazawa-sensei was such an inspiration.”

One afternoon in the back of a Kyoto temple Jack found the charred remains of a kendo mask lying in a fire pit. Its facial frame of metal bars was intact, but the leather fittings to cover the player’s head had mostly burned away. With the avian urge that leads him to scavenge objects worthless to passersby and transform them into elements of his own dwelling, Jack picked up the smoky remnant and brought it home. Ideas grew slowly: First he wove the mask’s bars with grilles of brass and copper wire, staining and burnishing these for highlights. Then came small pieces of leather, carved bone, beads of turquoise, a mane of dry grass and a rough crown of stems. Incorporating what he had learned from Noh mask making, he created a whole new form in what is seen by many as his most fascinating sculpture.*

One of the few visual artists who has collaborated with Madson is sumi-e painter and longtime Kyoto resident Michael Hofmann. “I see Jack as a measure of integrity,” Hofmann has said. “The craftsmanship, the knowledge of materials. Jack can envision like an inventor. I’ve seen firsthand the open-ended receptiveness that goes with the vast array of tools, techniques and aspects of design at his disposal. And also a certain playfulness. Jack’s humor comes in some sense with the colors he uses.”

Finding Phantoms

[S]cavenging prowess, invention and humor also distinguish Jack’s photography. Among his reams of breathtaking slides, mostly shot on journeys through Asia and Europe, is an extraordinary store of “found images” — super macro close-ups taken anywhere at all, often on excursions to Japanese junkyards. “I remember somebody complaining once to Frank Lloyd Wright, ‘Hey, there’s a crack in the wall of your building.’ ‘Oh no,’ Wright says, ‘that’s a line put there by nature.’ Well, things do simply happen that have balance, mystery and other qualities. And for me that became an inquiry. Up very close, the rectangular frame of the camera makes an enormous difference, revealing and releasing nature’s overlooked art.” There’s rascality here as well, especially when Jack projects these images onscreen as the closing sequence of one of his evening slide shows and his entranced viewers try to wheedle out of him what the original subjects were. Sometimes he fesses up. I first met Jack, in fact, at a jam-packed slide show party in his Kyoto home, circa 1984.

“His shows are nothing short of legendary,” says Michael Hofmann, whose friend, the Berkeley photographer John Pearson, showed Jack how to use a pair of projectors and slowly dissolve between slides to combine images. The alchemy of Jack’s approach, which began in serendipity, is that he sequences some of the slides so that when the darkest parts of the first absorb the brighter parts of the second, phantoms fleetingly appear — like the brooding form of a water buffalo — that cannot be seen in either slide.

It is late afternoon in Felton. Eiko and I are in the kitchen, where just outside the window a feisty hummingbird pays a visit to one of several bird feeders. I turn to watch Eiko dance freeform around the kitchen as she fixes one of her superb and healthy dinners, and I marvel at how ageless she seems. Here is the buoyancy that perfectly offsets Jack’s seriousness, which can swiftly turn to stubborn ill temper when anything tugs him away from his work. It is Eiko who keeps Jack young: Eiko’s ardent support for his art, her sparkling eyes and zest for life, her devoted attention to nutrition. ‘Genius,’ I’ve learned, derives from the Latin for ‘guardian spirit.’ What a pair these two are!

In the adjacent living room, amidst more of his art works, Jack is intently preparing a musical soundtrack for the slide show party tonight. Local friends are coming to dinner. He has asked me which country’s pictures I’d like to see and I’ve chosen India, the land he spent a total of nearly a year exploring while based in Japan. Here is how that series of migrations began, as Jack recollects it in a recent email:

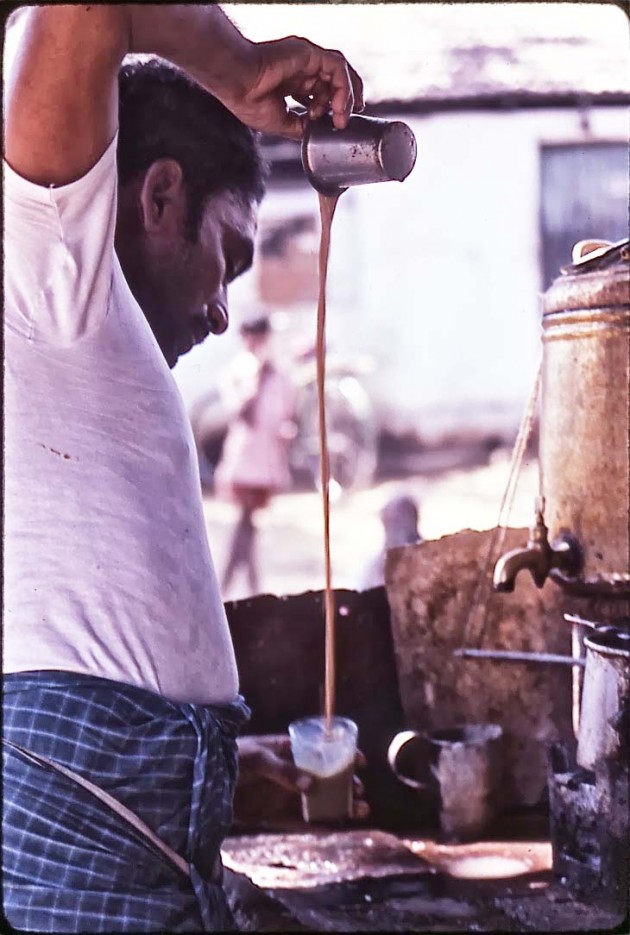

“My first trip to India was the last leg of a five-country sojourn in the spring of 1972. I left Kobe on a British freighter, one of three or four passengers. We stopped for a short time ashore in Hong Kong and similarly in Macao. I left the ship for good in Singapore, spending a few days there, and then, by bus and hitchhiking, up the less traveled east coast of the Malay Peninsula, stopping a week or so at the enchanting Thai island of Ko Samui. I continued north to Bangkok for a spell, then on to Chiang mai, over to Burma, oppressive Rangoon, and ethnic, historic Mandalay.

“I landed in Calcutta midday, cleared customs, found several people to share the long taxi ride into the city, stuffed our baggage into the scarred, dusty trunk and set off. I was coming from Japan, where we didn’t even have what looked like used cars, much less old taxis, which even today are always spic-and-span with the driver wearing white gloves. My first, well-used Indian taxi was shabby black and yellow, as if it had been born that way. One of its windows didn’t operate, remaining partially open through the heat and varied aromas. There were empty round openings in the dashboard with wires hanging out, some beads and a deity alongside flowers lying by the windshield. The driver was wearing a big red turban and honking the horn incessantly. His beard was held up tightly to his jaw by a close-fitting net and he wore a simple steel bracelet. I would learn that this attire identified him as a Sikh, an offshoot of Hinduism centered in Amritsar, in northwest India.

“Calcutta was a heavy experience, but one that I relished. Even the English Fairlawn Hotel with its air, all the lights, shadows, sounds, smells, was intensely Indian. I wondered if my senses could rest, even in sleep.

“The thousand-mile train trip from Calcutta to Madras in the south I would come to know well. Madras! …Bustling, dirty, center of art and music, flowers and bougainvillea, spicy food, many children in rags, others with shiny combed hair and white shirts, gypsies, rattling buses held together with hope and wire, exquisite bronzes in the museum, a movie industry, home of the many-stringed veena and bharatanatyam dancing, stone temples of great antiquity and gods galore, though it seems that six or eight of them pretty well satisfy most needs. Madras is where I found friends, a music teacher for sitar and a mentor. I would return here and over time get to know Madras better than any other Indian city.

“One influential impression was confronting, even touching, something that gives the sensation of being impossible: the ancient Hindu stone temples of Southern India, with their architectural dimensions and weights. The main temple at Tiruvannamalai, seen from a distance, is an imposing trapezoid rising from a massive base, adorned from top to bottom with hundreds of sculptures in detailed niches that diminish in size as they near the top. Getting closer, you see it’s constructed of huge stones perfectly cut and fitted together, carved with images of Hindu deities like Sarasvati, Vishnu and Parvati. You need to step back ten yards or so and point your nose to the sky to see to the top. It’s a long way up, about 100 feet, and you’re told these blocks of stone each weigh about eight tons. So, you look around and conclude that they surely couldn’t have been put up there by these people. Then, finding yourself unsatisfied with that meek observation, you consult the temple elders, hoping to find a satisfactory answer. The only near-plausible one is that the builders constructed an earthen ramp miles long and somehow nudged these huge stones up the ramp to the top. I later found there’s a temple of the same style farther south in Madurai, 180 feet high, with a top stone that weighs 80 tons! To picture something of equal weight, imagine 47 Ford Mustangs, all in a lump, somehow being raised fifteen stories high in the 17th century!

“It’s the space and time between observation, questioning and an engrossing awe on the one hand, and then the satisfaction that comes with intellectual understanding on the other, that I find exhilarating and inspiring. In a smaller way I find that a half-finished, unsolved painting touches on this. One time at home in Japan I spent some weeks designing what I thought should become several versions of a perpetual motion machine. I made careful engineering drawings and even a prototype of one. I knew perfectly well, without dispute, that perpetual motion is considered impossible. What I didn’t know was why my idea would be impossible. With the drawings and model I came to understand with perfect clarity the errors in my thinking. Then I was happy and satisfied. That area between the question and its answer is where I like to return as often as I can.

“Another result of that three-month sojourn came when I was leaving India and returning to everything that was not India. The profound shift left me with a mild kind of culture shock, perhaps more accurately expressed as a euphoric tension. In any case, it changed the way I looked at and considered events and relationships. I gradually came to use more combinations of yellow, orange and red and less blue in my paintings. The most enduring change was that I stopped, immediately, my subscriptions to the daily newspaper and a news magazine. They now seemed frivolous and not good for my psyche. I have never subscribed again.”

Jack also came home to Kyoto with his own sitar, a challenging instrument he would spend years blissfully learning to play. So devoted did he become, so wrapped up with this musical mistress, that he actually began to neglect his painting. One chilly day it dawned on him: Classical Indian music was so demanding, a choice would have to be made. Giving up the sitar, he returned unequivocally to his easel, resuming gallery shows with a string of successful solo exhibitions at Kyoto’s Shibunkaku Royal Gallery. Yet since music has always been elemental to Madson’s visual art — “melodic phrases, degrees of intensity and subtlety, transcendent things I relate to my paintings” — it’s no surprise he later picked up harmonica, pennywhistles and flutes, even returning to Indian music via the bansuri, and with local guitarist and friend Masao Sato producing some limited–run CDs, after studying with bansuri master Deepak Ram — all of this after co-migrating to America with Eiko, who plays piano.

![]()

The trees along Felton’s river gorge stretch upwards into a night sky spread with stars, a perfect finale to Jack’s slide show. His party guests have gone home. As I quietly soak in the backyard hot tub, I realize how like a tree he is, with his many limbs of talent branching out again and again, sending new leaves and blooms into the air. Then a sharp-eyed peregrine falcon glides overhead and alights on a nearby bough. With this, Jack’s portrait seems complete.

Jack Madson passed away peacefully on August 28 2013, age 86.