[K]yoto belongs to the rain. Not a place of brilliant sunlight, it is often sadly gray — an older woman who causes one to remark how beautiful she must once have been. Sit on the porch for a while in a lonely Kyoto garden. Watch the sad, sad rain drizzle across the silent pond whose master long gone designed it for days like this. Days when melancholy clings like crows to wet pine branches. When the leaves are greener, the moss fluorescent against wet stones hewn two centuries ago by masons forgotten in their own time. Feel the rain. Let it dampen your hands and face. Watch it drip from the roofs of thatched tea huts into the muddy pond. Kempt, but unkempt, the garden has a mind of its own. The trees are taller now than planned. A crane appears like a ghost in a dream, rests on the bridge for an instant and is gone. Things die and are replaced. Branches break and fish get old and scarred. Sit here for a moment on an autumn afternoon, surrounded by art and poetry, frozen in this moment — enough to make a young girl cry.

In the quiet frost of daybreak, a young monk swishes the last leaves of autumn from the stone path into a pile of smoldering dreams. Every last one goes up in a spindle of smoke — twisting, writhing through the tall pines to freedom in the morning sky. How he envies its unfettered ascent. He’s been up since 4 a.m., his frozen pink toes pretending not to ache in straw sandals. Shaved head, dark monk’s robes, and today’s lesson in the value of selflessness — difficult to take for a restless young man who’s just inherited his father’s country temple. He’s been sent to this famous monastery to learn the family business. Like it or not. The Zen riddle he’s been given to ponder? Is not change the only thing that’s changeless?

Here on Sanjo-dori a man slices bamboo with a tool he made from the handle end of a samurai sword he found in a flea market twenty years ago. He makes me a flower basket and reveals, by the way, that smashed river crabs are the best cure for breaking out in hives when you work with natural lacquer. Something to remember.

Elsewhere, the tofu lady cackles at me for not stopping by in six months. She plops a cube of jiggling white protein in my green tupperware box (everybody brings their own), and insults my beagle again by asking why he’s put on so much weight. “What’re you feeding him? Not that canned dog food stuff!? So that’s the problem.” All the neighbor ladies are lined up now with their boxes, waiting for a block of the world’s best bean curd. They do not shop for this at supermarkets. You can’t get it there.

Back at home, the neighbor slides open her gridded wooden door and steps over the threshold with a bucket and a dipper to water down the sidewalk in front of her home. Not as much the genteel custom observed by tea masters to welcome guests with dewy pathways, this is a left-over from the old days, not so long ago really, when you had to keep the dust down on Kyoto’s backstreets. Everything’s paved now, but it’s hot today, muggy and hot, and they say the very sound of the splash makes the whole block seem cooler. So they say. There’s air conditioning now, but they don’t like to use it. One should be hot, after all, in the summer, cold in the winter. It’s only natural. The old lady at the sweet shop puts an extra bean cake in my bag every time I visit her shop, and asks me every time why I have no children. That, too, is only natural.

Kyoto is a personal place. A place that takes time to get to know. The layout, an 8th-century Chinese design, is simple enough and easy to manage: a grid of streets running north-south, east-west, with the old Imperial Palace in the center. The whole city is intersected by the Kamogawa river just east of the palace and bordered on three sides by mountains. From the train station on the south side stretches a plain that runs all the way to Osaka. Along the foothills to the north, east, and west lie most of the famous temples and villas: Kiyomizu-dera, Nanzen-ji, Ginkaku-ji, Kinkaku-ji, Ryoan-ji, Shugaku-in, Katsura-rikyu. But passing back and forth across Kyoto in buses or cabs, you can only taste the frosting: the exquisite gardens, the trimmed and polished villas, the gilded treasures of art and history.

The people are what this city — any city — is really all about. The people and the way they live in the old neighborhoods: close and comfortable. Comfortable in the sense of feeling always at home. The back alleys of Gion, the geisha quarter. Of Nishijin, the textile neighborhood, where the sound of looms at work still haunts the changing streets. At a table outside on the porch over the Kamogawa in mid-summer at a little restaurant on Pontocho, where you can sample the night air, taste the tempura and feel the furyu, a natural chic… enjoying the languid evenings, paper lanterns, and cool river breezes that have floated here for 1200 years.

Old Sakamoto-san serves his meals as if each time were the first, forgetting the pickles (or the main course), and stopping in front of the television to watch the last match of the sumo tournament. The little restaurant is dark and small and smells in summer of a vague permissiveness with cats. Every day Sakamoto’s wife and son chop vegetables and grill fish and smile in true kindness on their motley crew of customers: old ladies who live alone, college students away from home, and foreigners with no place else to go. The food is simple and simply superb, and if you belong to the neighborhood and eat here every night, you eat for half price, but you’d better finish all your rice. “Taberaremasu ka?”he always asks, as a humble courtesy to his guests or as if he’s checking to see if his wife forgot to add the shoyu. The neighborhood gathers here each evening, watches T.V. and slurps its soup. Warmed against the cold and loneliness, they trundle off together to the public bath.

Splitting out another stave by hand, Miki-san grins patiently at the umpteenth camera and demonstrates the process of making wooden buckets, the kind no one uses anymore. He’s a curiosity now, a quaint glimpse of “the real thing,” seated on the floor of his cramped old shopfront using hands and toes to crank out props for samurai films and souvenirs for wealthy tourists who are bored with most of what money can buy. His neighbors are the only ones who really use his services. A few of them are still frugal enough to bring him worn-out buckets to repair, and he loves them for it. And yet once again, he will lead the tourists out to the back of his creaking wooden house without hesitation, past the well and the wood-burning stove and the outdoor shower and toilet that speak to his affluent guests of poverty, though he does not. He will never see the things they can’t live without, the dishwashers and garbage disposals and walk-in closets, and he has no interest in them. He is interested only in “working till he dies” he tells the cameraman, fussing with his potted plants out back “because green is restful for tired eyes”. He is as close as one can get to the past. With no son and no apprentice, he sips his sake and waits alone in a cold dark room each night for dawn to give him another day with his precious wood, another day to smile and teach what it means to love your work.

Advertisements on the mirrors in the sento: Get your clothes dry-cleaned at Takeda’s… Acupuncture and moxa treatments from government licensed Dr. Sato…. Traditional Kyoto-style soba noodles delivered steaming hot to your door… Get your pants mended at Tanabe’s, the “Clothes Doctor”… and don’t forget to lock your valuables in the wooden lockers in the dressing room (not that anything’s been stolen within living memory). Signs above the baths: No smoking (you would have cigarettes?)… Don’t get soap bubbles on the person sitting next to you… Those with sensitive skin, heart problems or weak physical conditions beware the temperature of the water… No splashing, and no running, children… No dipping buckets into bath water… Observe the rules of public courtesy as prescribed by the National Association of Public Bath Owners. The furnishings: massage chairs always filled with elderly ladies engaged in easing their pain… one vintage bubble hair dryer, one orange plastic community hair brush (in case you forgot your own), and a stack of extra bath buckets for the same reason. Ladies everywhere, ladies shaving their legs and faces, scrubbing their heels with pumice stones, lathering themselves into an oblivion of bubbles, rinsing copiously, washing again, rinse again, apply liquid face soap with little round brushes, don’t forget to use the wash cloth, shampoo your hair, rinse again, brush your teeth, slip into the bath, soak… soak, rinse again, ring out your wash cloth, rinse off the stool and ledge for the next person, wipe off the water with a wet towel (not dry), and don’t drip water on the reed floor of the dressing room on your way out. If there were ever a water shortage in Kyoto all these women would go insane.

The pounding sound rose slowly in his mind until he realized it was the hammer again beating progress into the wistful Kyoto neighborhood he called his own. The web-toed carpenters in their lavender jodhpurs were still toting long wooden poles here and there, lifting them in place well past quitting time. They had been at it since dawn and would continue until the half-light and smell of grilling fish persuaded the boss it was time to head home. There was much talk in the neighborhood of what the new building would be like: a love hotel perhaps, where company men would take their secretaries on Friday afternoons to add an element of secrecy and excitement to a seemingly bland coupling of organs. Perhaps it would be an office building, though it seems odd in a neighborhood like this where every road and alley is an extension of someone’s home.

The old man down the way isn’t happy with the new contruction. He stands grumbling as he waters the plants in front of the small orange neighborhood shrine, the gods of which are apparently under his self-appointed care and personal daily attention. Still begrudging his surrender, the barrel-chested ex-colonel coughs and hacks his way down the alley in his pajamas each morning to perform his final duties… watering the shrine, paying his respects and thanking the gods for one more dawn. He chases the ducks from his landing on the canal bed (nothing irritates him more than birds nesting in his bonsai). Except perhaps the new construction. Passing the gaping hole that had once been a weaver’s house, he feels the hollowness of soul that a man gets when something that has long been with him is suddenly gone. His wife died last spring and now this. What would stand in its place now… a Pachinko parlor for slovenly students who would clutter his path with a dozen broken-down motorbikes? He barks at the ducks and fusses with his miniature pine in disgust.

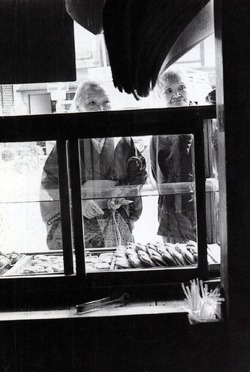

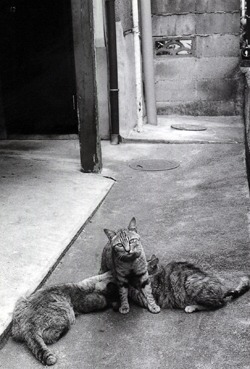

Crazy old woman across the canal (the“Cat Lady” the kids called her) swishes her head back and forth, talking to the strays that now haunt her window ledge. The abandoned house had sheltered all those homeless cats, and now like bums thrown out of the Bowery, they huddle constantly on her creaking ledge. She can’t resist them; they are her only companions, and the shopkeepers on the market street give her free scraps of fish to feed them. Everyone knows she’s not quite right these days, muttering constantly to herself and her menagerie. But the neighborhood takes care of her. She sits out on the old bridge at the canal in the evenings with her dogs and cats clustered like reverent disciples at her feet. She talks with the passing neighbors, feeling for an hour or two as if she belongs. Flustered at the hammering, she draws her head into the second floor window, turns up the TV set and calls in her aging dogs.

Out on the canal, a troop of small boys scrape the river bottom with flimsy nets, scooping out the increasingly suspicious hordes of pollywogs hoping to survive another onslaught until dinnertime when their antagonists retreat — reluctantly — for supper. An old bent woman walks an old bent dog, carefully scooping up after him, not to elicit whispers from eyebrow-lifting neighbors always on the lookout for infractions of the local order. Tonight there will be fireflies, in a few weeks dragonflies and fireworks to look forward. Guess we can call this one a day.

The light is on downstairs at a dyer’s supply shop. Mr. Hasegawa is up late as usual working on his accounts. With the depression that has hit the traditional textile industry, he must work very hard to stay afloat. His office consists a single gray metal desk that sits on the cold concrete floor inside the doorway in a space about nine feet square. The walls around him are covered with stacks of account books and catalogs. His daughter studies English and his son has decided to carry on his father’s business. The tatami mats in the entry room are worn and covered now with cardboard to protect them from further damage. With no space for storage, this is the only place to stack their shipments. They are not wealthy people. Mrs. Hasegawa takes care of her 90-year-old mother-in-law in the room beside the entry, she is blind now and has difficulty walking. Every day Mrs. Hasegawa reads her the morning paper, fixes her meals and makes sure she is comfortable. She writes a column for the local paper about caring for the aged. She always smiles a welcome to her daughter’s foreign guests, and offers them a cup of very fine Uji tea (their only luxury) and a sweet. No one goes home empty handed from their humble home… Apples from a customer in Sendai this time, carefully wrapped one by one in tissue.

Somewhere down a tunnel of wooden-walled houses, tucked away upstairs beneath a hot tile roof, a silk dyer dabs his brush in vermilion and fills in the 253rd maple leaf on a strip of kimono silk four meters long. He’s nearly finished. He’s been up all night. It’s quieter then, and cooler. His wife and son have gone to bed, and the only sound left to disturb him is the high-pitched whine of the yaki-imo man’s loud speaker, peddling baked sweet potatoes from the back of a converted truck. He is tired. He has been painting yuzen patterns on kimono fabric since he turned 15, and he doesn’t make much money. He is not famous, not even known. He is carrying on a tradition — the only life he has ever known. Of this he is proud.

This morning the hills of Kyoto are shrouded in the gray mists of autumn, the same one poets lament each century. There is indeed a beauty here, and certainly a sadness. The real beauty lies in the hands of the people who populate the narrow backstreets, work in the old shops, and make the things of long ago. The city has its problems; all cities do. But its people also know the secret of surviving together in a dense urban environment, the one that wears the face of the future. To let them and their convoluted culture slip away unnoticed is a sad mistake for the world to make.

When Kuwano-sensei learned that the young foreigner was eager to study ink painting and knew she had no money, he agreed to take her on for free. They met on Saturdays and the old painter taught her what she needed most to learn. He spoke no English and she no Japanese, so they sketched together and somehow worked things out. One spring day she went to him with an ink painting of cherry blossoms, proud of her progress with the brush and eager for his praise. “No good,” he said, without flinching. “Go back to the pencil. This is not about skill. You must show me that you understand the life force that flows through the branch of the tree and into you.” He always knew. “And besides,” he said, “cherry blossoms are not the real voice of spring. It’s the fuki-no-to, the tiny green shoots that breakthrough the last snow of winter. During the war, we used to eat them in the countryside. When you see them, you know winter is not forever. You know spring will come again… and you have hope.”

Author

Diane Durston

Author's Bio

DIANE DURSTON is the author of Old Kyoto: A Guide to Traditional Shops, Restaurants, and Inns (Kodansha International 1986) and Kyoto: Seven Paths to the Heart of the City (Kodansha International 1987). Another book, The Living Traditions of Old Kyoto, was published in November, 1994.

Credits

Photos from the book: Streets of Kyoto by Kai Fusayoshi