IT IS ASTONISHING how a few words can change the way we see the world. They can imbue us with that extra dash of hope that makes each day shine a little more brightly, or strip it of any glow whatsoever. Words can give us a glimpse of true beauty, inspire us to greatness, instigate social change through a single speech; yet conversely, words can incite anger and hatred, spark horrific wars, and rob even our happiest moments of any fulfillment. Words are what we frame our experiences with and the labels we attach to our memories. It is easy to forget how such tremendous power rests in a tool we wield daily, and the influence it has on others. The person who turned by entire world upside down nearly fourteen years ago certainly had no idea what a huge change he had caused me — and the catalyst had only been four simple words, five syllables.

It was on the third night of February, Kyoto’s coldest month, that together with my parents I made my way towards the ominous silhouette of the Mountain. I’d pulled the sleeves of my jacket over my hands, but the winter chill still pierced through. It was snowing gently. In the dark I could feel the flakes brushing against my face, getting caught in my eyebrows or melting on my outstretched tongue. Here and there the snowfall revealed itself as a slowly swirling cone beneath a solitary streetlamp, a dusting upon the asphalt that dissolved under each footstep, or a faint glaze on the tiled roofs and pines that lined the road. It fell so calm that it was like watching a pale silt settle to the bottom of a deep pond.

The night was so quiet — the usual drone of the evening traffic was muted, the rumble of the faraway train muffled, winds softened, and words were whispers. Yet my doubts, and the pounding of my heart, resonated louder and clearer than ever.

The third night of February was the most dreaded time of year for all the children in Kyoto, and the Mountain was the worst place you could be. Even so, it was where we ended up, some of us dragged there by our parents, others compelled to come by some grim fascination. We had good reason to fear this date, for it was on this special night that the Oni, the demons and ogres of Japanese myth, descended from their mountain lairs in search of children to eat. As frightening as this was, we did not run or hide. With strength in numbers, we would soon gather to face the Oni at the mountaintop shrine from which they always emerged. It was only through this solidarity that we survived each winter.

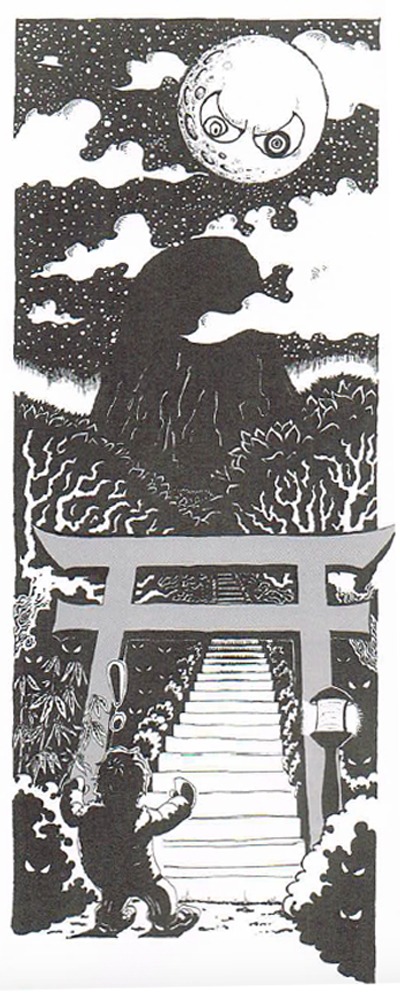

Before long I found myself at the Gateway, a lofty stone structure that stood at the based of the Mountain, marking the start of the path to its summit. From its threshold a set of tall steps rolled out like the tongue of some great beast. The stones were smooth, sculpted by thousands of feet that had trod upon them over the centuries. As I clambered up, one by one, I vaguely wondered if someday those steps would be reduced to nothing at all.

At the top of the steps was a comforting sight to behold, and one of the reasons why we children all willingly came here at our peril — the road ahead was crammed with people bursting with light and life. Both sides were lined with food stalls, heated tents, and shopkeepers hawking wares on hastily spread tarps. The road stood out as a river of gold against the black of the night. I followed my parents into the crowd of faces, where voices and breaths turned to vapor and eddied around me. Despite what lay ahead, I couldn’t help but be enthralled by this waltz of activity unfolding at every turn. To my left the fried noodle man was plying his trade on a huge, sizzling hotplate that exploded in steam whenever he threw in generous dollops of his famous pepper-laced sauce. To my right was a pudgy old lady making yakitori, bite-size chunks of check and leek on wood skewers. She turned them over hot coals, occasionally brushing on a sweet marinade. Farther up was my most favourite of all, the stall with the steamed potatoes so soft you could easily mash them with the plastic forks they came with. These were sprinkled with sea salt and crowned with a drooping block of melted butter. Such scents and marvels can drive any any concern from the mind, and for a while I was carefree again.

When my parents bumped into some of their friends, I ran off to explore the outer edge of the road. From outside, the stalls with their plastic sheets looked just like a long wall, glowing from within like a paper lantern, interrupted only by the occasional gap just wide enough for a child to slip through. It was an exciting vantage point. On one side there was light, noise and everything familiar; on the other, twisted branches and scattered patches of moonlight, bramble as deep as the shadows, and all the mystery of the wilderness and of the night —the edge of an abyss! From this border I peered into the inky depths, imagining what creatures lurked beyond, until the whole thing reminded me of the Oni.

I quickly found my parents who, thinking I was up ahead, had walked onward. My father’s hair, still blond back then, was easy to spot in the crowd. My unpleasant realization had put me back into a somber mood. I did not pause as we passed the tent with the cork guns and prizes secretly weighted not to topple, nor did I glance at the tub full of goldfish, where you kept your catch provided you could scoop it up in a flimsy paper net. The shops grew sparser until finally they dwindled out where the road came to a clearing. At the far end, flanked by two blazing torches, was the first in a long succession of wooden gateways.

These gates were small than the one at the foot of the Mountain, but still much taller than me. They were painted in a chipped and faded orange that now regained its original vibrancy in the firelight; each was like a rung that could take one deeper into the darkness beyond. Indeed, the blackness they framed was completely inscrutable, yet strangely mesmerizing. This was the entrance to the shrine, and the place from which the Oni would soon emerge. More and more people filtered in and before long a crowd had formed, of which I was content to remain at the rear. The moon retreated behind its veil of clouds; each minute seemed an eternity. Every sound elicited a nervous glance toward the gates,each false alarm a momentary relief. The anticipation was palpable, growing by the second.

Before the coming of the Oni, an excited murmur swept through the crowd. Tentatively curious, I made my way toward the front, from where I’d be able to see the gates. Several screams rang out before I got there, and next came a guttural roar that chilled me to the bone — it was THEM. In that instant, it took every shred of self-control not to simply turn around and run. Instead, I was surprised to find myself throwing each trembling foot ahead of the other, ears ringing and heart hammering m my chest, until I burst out into the front row. A soon as I got there, I realized what a bad idea it had been. Not five yards away were three of the most hideous creatures I had ever seen.

Their faces twisted in a permanent grimace. With scimitar like tusks and beady eyes that darted from face to face, the Oni advanced slowly into the crowd. Two bony horns protruded from their manes of coarse, filthy hair, and each had a different shade of scaly skin – one red, one yellow, and the last blue. They brandished huge iron clubs, which they swung over their heads with ease. When they spotted children, they charged up close and bellowed, barked and roared in their faces, beating their clubs against the ground. Many children went hysterical, while others simply froze or bolted. The closer the Oni came to where I stood, the more excruciating each moment seemed. I didn’t have to wait long. The yellow Oni turned toward me, and for the briefest of seconds, our eyes locked. My stomach lurched as I saw him turn from the bawling baby he had just scared witless and head straight towards me. Each step he took seemed to last forever. But then he was there, that awful toothy scowl mere inches away, and I braced for the worst.

In a broken accent, he uttered four words: “Do you speak English?” I blinked, and in that fragment of a second after my eyes had snapped shut, it was more than my eyelids that began 10 retract, but a curtain, a shroud, a fog over my sight that had started to lift. By the time I had opened my mouth in reply I had new eyes, and they took in new scenery. The fearsome Oni was now merely a man in a mask – stripped of all his mystery and peril, as would be the ghosts I had heard some nights in mr house; tricks of the wind. The face that had stared at me from the staircase door would become but a pattern in the wood grain, the eyes that shone from the thick of our back garden, our neighbor’s cat. The patter of footsteps on the roof outside my window just twigs falling from the branches above, and that thing that lurked in the corner of my room once the lights were out; a pile of dirty clothes, a mound of toys, a rumpled backpack or a stuffed animal with its button eyes, animated by the moonlight. The thing about such monumental changes in perspective is that they’re so big you don’t even realize they’ve happened, until you start looking at every detail again, and finding each different somehow. For me, that full realizatio n would come a little while later. For now I was in on this joke, and my preoccupation with being eaten smoothly turned to that of finding something to eat. Maybe those steamed potatoes.