While physical entry to Japan by non-residents is currently prohibited, our latest issue, 100 Views of Kyoto – A Tribute, is a convenient alternative way for overseas readers to visit (or revisit) Kyoto.

Cutting edge post-Covid tourism? Not really. Kyoto has in fact been a popular destination for virtual travel since way back in 1780 (or was it 1786?), mid-Edo period, when the Miyako Meisho Zue (Famous Places of the Capital, Illustrated), was first published. Edited by Akisato Riko, in six volumes, with over 400 full-page or double-page depictions of meisho — well-known sights — by woodblock artist Takehara Shunchōsai, it was followed in 1787, due to popular demand, by an additional five-volume set, the Shin-Miyako Meisho Zue, and in 1799 by the Rinsen Meisho Zue (Famous Gardens of the Capital, Illustrated). The immersive visual content of these publications was accompanied by detailed local lore and apt literary quotations and allusions.

According to Shirahata Shozaburo, a scholar at Kyoto’s Nichibunken (International Research Center for Japanese Studies), “meisho” originally denoted “a place with poetical associations” — locations connected with the aristocratic pursuit of waka verse. Over time this connotation was lost, and the meaning became simply “places that attract mass interest.”

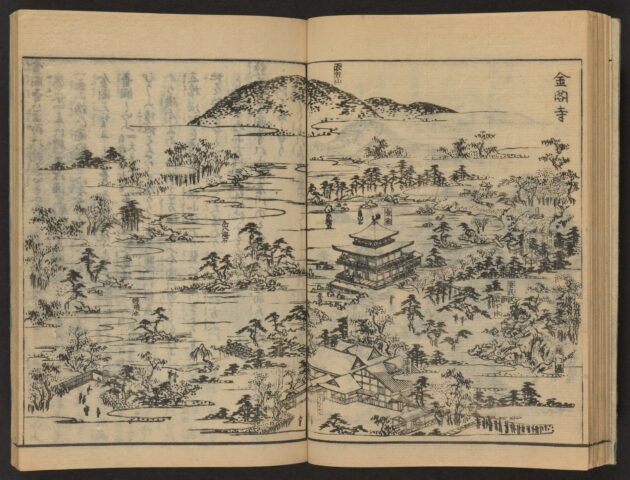

Naturally, many of these famous sites/sights are as popular now as they were then, and can be easily recognized in their current form within these publications.

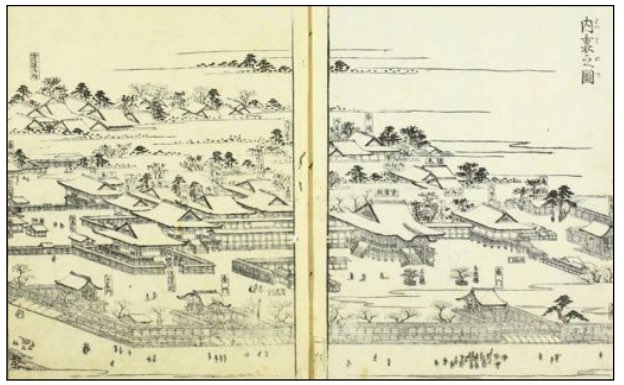

The woodblock images are so meticulously detailed that it’s often possible to find exact representations of structures that have since been lost to fire or other calamities. These include even entire complexes such as the Imperial Palace that was engulfed in one of Kyoto’s three most destructive conflagrations, the Great Fire of the Tenmei Era, in 1788 — the year following publication of the Shin-Miyako Meisho Zue. (Within two days, a swathe of downtown Kyoto including Nijo Castle, the Sento Gosho, Higashi-honganji and Nishi-honganji Temples, over 200 other temples, and more than 36,000 houses were destroyed, and the Meisho Zue gained immediate additional and unexpected significance as historical records).

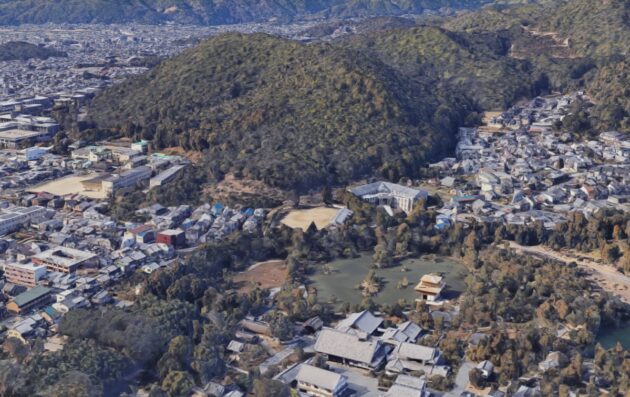

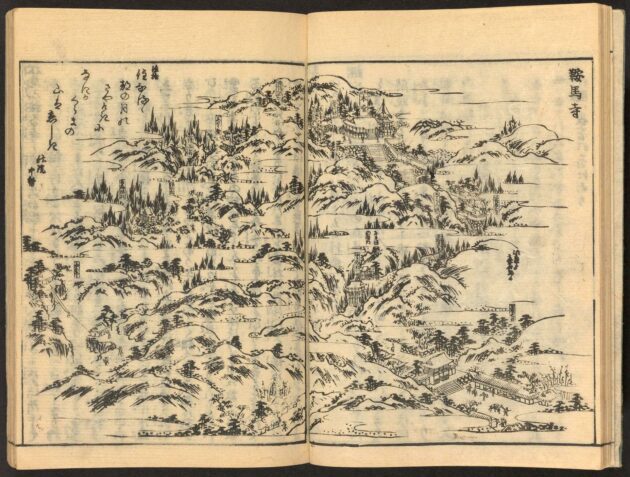

Notably, in a tradition that extends to present-day on-site painted map signboards of temple precincts, every shrine or temple appears to exist surrounded by pristinely scenic forests and mountains, even though in the mid-to late-eighteenth century, Kyoto was Japan’s third-largest city, with a population of over 300,000 people. Today, that figure is closer to one million, and the formerly far-reaching precincts of even major temples have contracted, while urban sprawl has encroached on formerly unspoiled landscape views.

Some scenes from the periphery of Kyoto seem timeless. Ginkakuji’s garden still melds seamlessly into the forested foothills of Daimonji-yama, and the sacred mountain of Kurama — the haunt of legendary tengu, together with Mao-son, a deity who reputedly descended from Mars just 6.5 million years ago, and more recently, Reiki healing practitioners — remains much as it was when Sei Shonagon described it in her Pillowbook: “The road to Kurama is a winding path; at a glance the distance appears to be quite near, but it is quite far.”

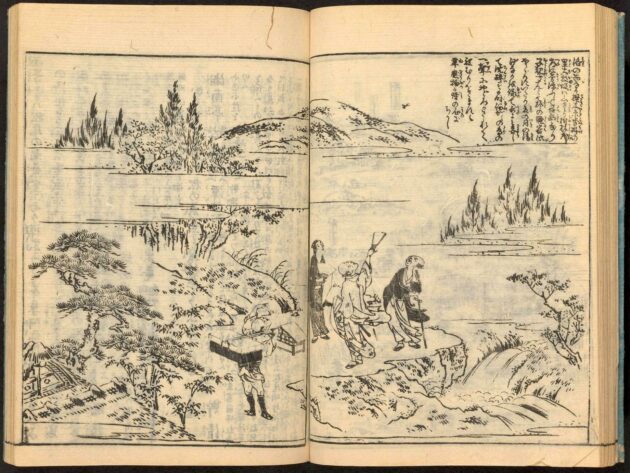

Kurama-dera, in the northern hills, from Miyako Meisho Zue. Apart from the loss of the small pagoda, and addition of an unobtrusive cable-car line, this scene has hardly changed…

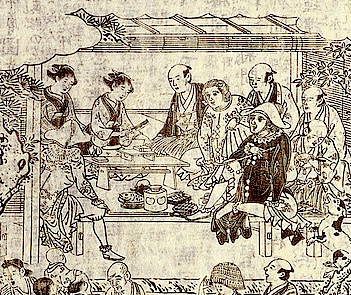

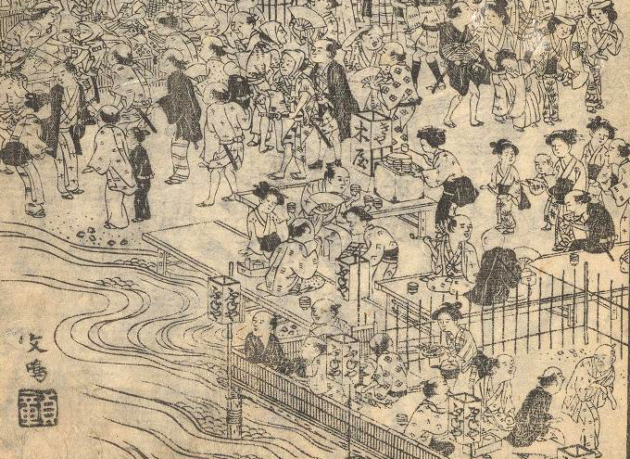

Or, according to Wikipedia Commons: a “performance of cutting tofu quickly while being entertained at Nikenjaya in Gion.”

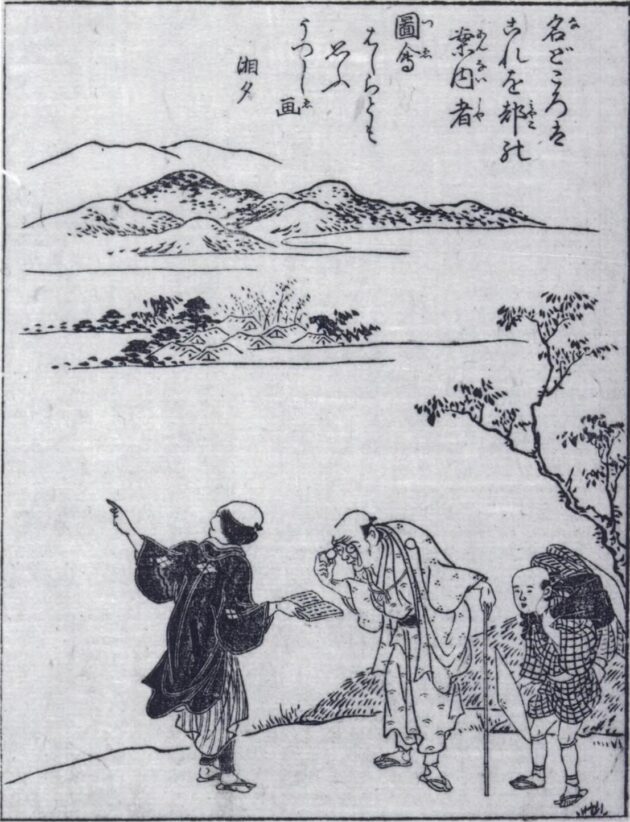

Despite its price (estimated by Shirahata to have been the equivalent of 60 to 70,000 yen today) the Miyako Meisho Zue was a best-seller in its time, though its large format and many volumes probably made it impractical as a handbook for on-site reference. Instead, it allowed well-to-do purchasers to remain comfortably at home, avoiding the rigors of actual travel in those pre-Shinkansen days, while vicariously enjoying all the most notable attractions of Kyoto.

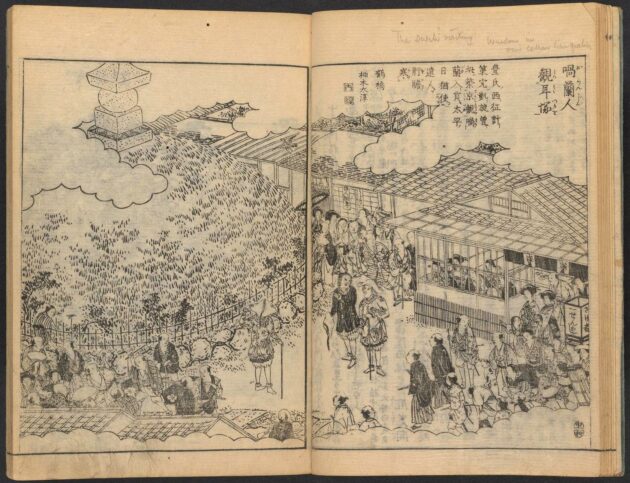

In addition to the semi-rural delights of out-of-the-way literary-associated temples, some coverage is given to local festivals and crowded popular events such as cherry-blossom or maple-leaf viewing parties. In one scene, several Dutchmen are seen at a restaurant in Gion; another shows foreigners being observed by curious townsfolk at Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s infamous Ear Mound (which still exists) in front of Hokoji (long-lost home of Kyoto’s Great Buddha).

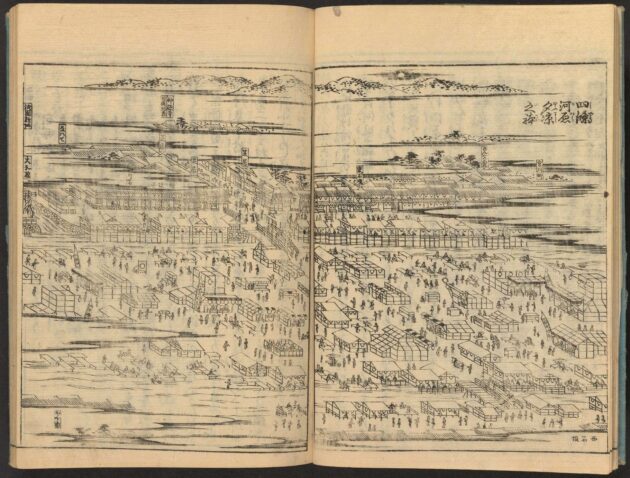

Other scenes reveal the delights of Shijō Kawaramachi’s fabled summertime entertainments, held on the dry riverbed. Robert Goree describes elements of Takehara’s depiction as follows: “Two ticket takers sit at the entrance of a tall tent below a banner that advertises kyokumochi, a kind of acrobatic show in which performers use their hands, feet, and heads to manipulate objects such as bales of rice in the air… An audience has gathered inside a roofless makeshift theater to watch an entertainer perform with a samisen on stage …” And “In simple prose, [Akisato Rito] describes some of the many entertainments to be found here, including storytellers, mimics, dogs engaged in sumo wrestling, monkeys performing theater, freely flowing sake, and wild animals from deep within the mountains — all against a background of ‘lanterns sparkling like stars, purple banners waving in the wind, the youthful moon shining bright, and countless fans waving.’”

Food for idle fantasy and yearnings to undertake the arduous trek to Miyako, indeed.

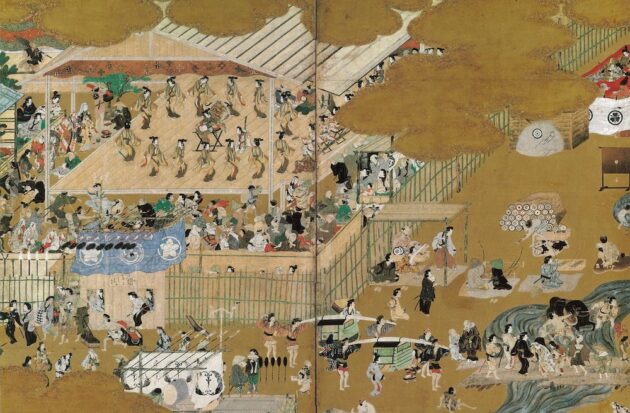

These fabulous Edo-era riverside entertainments also appear in comparative Technicolor in a genre of raku-chu raku-gai screen paintings, conjured up for a more exclusive audience.

These cutting edge media of their era, long employed as a means of virtual travel, now also enable us to virtually travel back in time.

Meanwhile, those of us physically here in the old capital often experience a kind of timeless simultaneity of multiple layers of succeeding eras, and preceding generations, infused with the richness of accumulated literary and visual arts in the long-celebrated cultural wonderland of Miyako/Kyoto—surrounded still by its fabled mountains, forests resonant with birdsong, and resplendent bamboo-groves.

The Miyako Meisho Zue and Miyako Rinsen Meisho Zue can be visited online at the Smithsonian:

Miyako Meisho zue (vol. 2-6)

Miyako Rinsen Meisho zue (vol. 1-5)

As another way to virtually visit Kyoto, KJ 100 includes a short selection of particularly recommended online resources.

Tourist consulting a guide book and a tour guide, from Miyako meisho zue