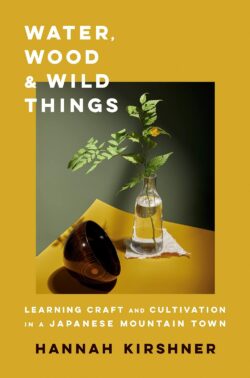

Water, Wood, and Wild Things: Learning Craft and Cultivation in a Japanese Mountain Town

by Hannah Kirshner. New York: Viking Press, 368 pp., $26.00 (cloth).

It was the writer Junichiro Tanizaki, in his book In Praise of Shadows, who famously described the mysterious beauty of a lacquer bowl when seen in the flickering shadows of a candlelit room, as being the epitome of the Japanese aesthetic. Indeed, so firmly is the art of urushi associated with Japan in the Western imagination that in many places lacquer is known simply as “Japan-ware.” Given its prominence, it might seem strange that so few Westerners have gone to Japan to learn its secrets. Maybe part of the reason for this reluctance is that most people break out in a bubbling rash when they are exposed to it in its raw state.

This does not stop Hannah Kirshner, however. Having grown up on a farm outside of Seattle, she is not afraid of itchy rashes or bubbling blisters. First arriving in Japan not for lacquer but for sake, she is invited to work in a friend’s sake bar in Yamanaka, in rural Ishikawa Prefecture. Like many foreign students of the arts before her, Kirshner is there to be a deshi, or apprentice. Japan is well-known for the strength of its master-student relationships. This requires great dedication on the part of the students, as apprentices are expected to look and learn—and not to make waves. And so, Kirshner learns the ropes of pouring and serving sake by listening attentively to the master.

Before long, she has also made countless friends in the hot spring town. Yes, she has a wonderful personality! Endlessly curious, she is not in Japan to change things, she tells us, but to learn. And she does this with great humility.

She next goes to work in a traditional sake brewery, becoming a kurobito (brewery worker). We see her wearing an industrial apron and rubber gloves, her hair tightly tucked into a hair net, as she is leaning deep into a vat, mixing the shubo starter by hand or taking the temperature of the moromi (sake mash). This experience leads her to tea ceremony and also the art of woodturning—and before you know it, we are following along as she explores foraging and hunting; paddy rice farming, paper-making, and lacquer. Seeking out these experiences as a journalist in order to document the culture of Yamanaka, she weaves together the stories of a community.

Having studied painting in university, Kirshner then relocated to Brooklyn, where she became a food writer and stylist. This background perhaps put her in the ideal position to understand the traditional culture of artisanship so prized in Japan. Known as shokunin, artisans in Japan remain tied to their local environment, using traditional materials and methods. From tea to sake, and from hunting to farming, in Yamanaka these activities remain relatively conservative, and male-dominated. Kirshner navigates this all with tremendous grace. She embeds herself in the tight-knit community, and her openness to its history, traditions, and people is admirable. One of her friends, who is a kannushi, or shrine keeper, reminds her that, “The Japanese spirit developed with nature, feeling the seasons, and accepting change.” And in this spirit, the people of Yamanaka welcomed an American lady into their homes and workshops.

In addition to the beautiful writing, her stories are interspersed with drawings she made and a variety of inspiring recipes, from miso-cured eggs and hunter’s stew to wild herbed dango and midnight fried chicken. Published during the Pandemic, when time took on a stretched-out quality, this was the perfect book with which to stop and savor the seasons and flavors of Yamanaka, and a lifestyle that is more deliberate and more deeply connected to place than our own.

Author

Leanne Ogasawara

Author's Bio

Leanne Ogasawara has worked as a translator from Japanese for over twenty years, in the fields of academic translation, poetry, philosophy, and documentary film. She has been contributing to KJ since 1999 — from poetry translations (Takamura Kotaro’s Chieko Poems in KJ 39) to interviews (Kyoto artist Daniel Kelly, in KJ 91) to articles (‘Traveling Through a Painting: Dream Journey over Xiao Xiang’, KJ 47, and ‘Nachi Falls’ in KJ 92, our Devotion issue). See also, her monthly column at the science and arts blog 3 Quarks Daily.

Credits