With unprecedented snowfall in Australia’s subtropical state of Queensland, hail storms in Mexico City and record high temperatures in Paris (45.9C) and Churu Rajasthan (50.8C), it is increasingly difficult to close our eyes to the consequences of global heating. When we see self-serving politicians and big business leaders in flagrant collusion, displaying no inclination toward implementing the desperately needed changes that the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is demanding, it is difficult not to succumb to pessimism. At certain periods in history, humanity has been more aware of its vulnerability, as in Europe during the fourteenth century when the Black Death decimated nearly half of the population in urban centers. The difference between these overwhelming epidemics and our present environmental crisis is that humanity itself is responsible, or at least those who are promoting and leading a hyper-consumptive life-style.

To cope with a crisis of such magnitude, it is natural to seek solace in one’s religious faith or succor in scientific literature on the subject. However, no matter how intelligent or wealthy we are, it is almost impossible not to be swayed by our cultural assumptions. No single spiritual practice or philosophy can adequately cope with the detrimental effects of global heating, but sometimes stepping outside our comfortable traditions can open doors and shed new light. Modern spirituality in its myriad forms has been inspired by the world’s greatest philosophers such as the Buddha, Mahavira and Laozi who lived during the Axial age when the introduction of iron weapons and social inequality engendered hitherto unprecedented levels of suffering.

Although there are great differences in meditation practices, mindfulness in particular has attracted the business community because it can significantly increase practitioners’ focus. Repeated clinical trials have shown that regular practice of mindfulness can reduce depression, anxiety and chronic pain. Sitting quietly while breathing in and out is a simple practice that anybody can perform on a daily basis regardless of cultural background. It is truly comforting to have assurance that we can experience tranquility and happiness if we let go of extraneous thoughts and attachments while being consciously in the moment.

Nevertheless, even these most noble of sentiments can be decontextualized and manipulated by authority figures. For example, the US and British military have begun increasingly relying on mindfulness to train troops to stay calm during combat maneuvers. The colonial-period Burmese Buddhist community may not have anticipated that insight meditation (Vipassana) which gave birth to mindfulness would be distorted by the very powers from which they were trying to liberate themselves. Clearly these military applications corrupt mindfulness by ignoring the ethical dimension of Buddhist meditation which is indispensably linked to traditions of non-violence.

Historically, even devout Buddhists have been led astray by nationalistic agendas, unfortunately. A notorious example is the shortsightedness of Rinzai Zen monks who adhered to Japanese imperial propaganda condoning violent acts against non-Japanese civilians during World War II. While many Zen monks did not support the war atrocities, the writings of Buddhist thinkers such as DT Suzuki show that they subscribed to the chauvinistic jingoism that brought about so much indiscriminate violence. The chanting of a mantra can relax the mind, but if one becomes attached to the teachings of a Zen master or a Hindu guru, for example, loyalty can turn into a docility that can ultimately be manipulated. Unless one has a resilient personality and sharp critical skills, it is easy to be swayed by the words of one’s master, as are Buddhist monks who live in communities that are cut off from daily problems of ordinary working people. “If we truly become mindful of our existence then our recurrent anxieties become not just a wave we watch pass through our minds, not something to be mastered in order to be a better servant, but a call to take action in order to be more fully alive,” argues Zoë Krupka.

Before China’s Cultural Revolution, it was not uncommon to pay homage to statues of Confucius, Laozi and Buddha within the same temple compounds. The syncretic nature of Chinese philosophy has provided people with resilience and a unique brand of relativism. Daoist philosophers have argued for centuries about the significance of the aphorism 知足常樂 “knowing contentment ultimately brings happiness.” The question for the top five percent of the world’s population, which controls most of the wealth and resources is “when is enough enough?”

Although Daoism has always opposed materialism and is tenaciously anti-establishmentarian, its veneration of nature and insistence on unhurried living historically made it unique among the Hundred Schools of Chinese Thought. (Zhuzi baijia諸子百家) Some of its anecdotes are cryptic, but the Book of Zhuangzi is noteworthy for containing imaginative parables that illustrate the radical equality that exists in nature. The first two Chinese characters that form the title of the opening chapter on Free and Easy Wandering literally mean “easy and unconstrained” (xiao 逍) and “long distance” (yao 遥). In other words, the playful wanderings of the mind constitute a critically important feature of human nature that is often suppressed and underemphasized.

The advantage of comparative religion and philosophy is that they can both relativize our convictions and offer alternative perspectives and solutions to the most pressing existential problems. As a counteractive philosophy, Daoism has always emphasized the need to be free of rigid concepts and strenuous practices that go against the natural order. In a playful tone, Confucian propriety is turned on its head in the Book of Zhuangzi as nature is placed above social norms that try to restrain our boundless spirit. Interestingly, over the centuries many Confucian literati became increasingly captivated by this “free and easy philosophy of mental wandering.”

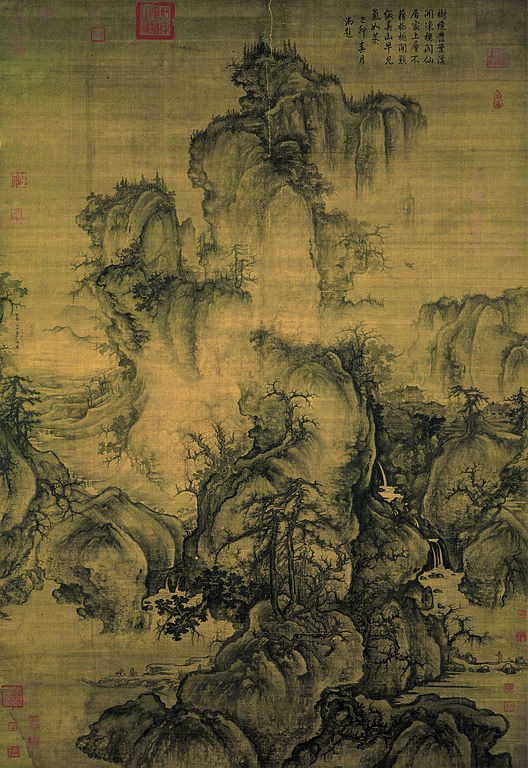

Since the Song dynasty, Chinese landscape paintings have served as mental constructs which enabled artists to envision an ideal harmony. The eleventh-century court painter Guo Xi of the Northern Song dynasty explains, “A virtuous man takes delight in landscapes so that in a rustic retreat he may nourish his nature amid the carefree play of streams and rocks. . . Haze, mist, and the haunting spirits of the mountains are what human nature seeks.” After the Mongol conquest, some Chinese literati painters even refused to serve their new rulers and depicted landscapes that alluded to stylistic statements of political protest.

“Early Spring”, Guo Xi

Meditation and intense periods of concentration can offer insight and wisdom, perhaps the mind also needs time to wander in selfless ease. Jonathan Schooler who runs a laboratory investigating mindfulness at the University of California at Santa Barbara takes a similar perspective “The challenge is finding the balance between mindfulness and mind wandering.” It is not too late for the wealthiest business leaders to realize that the destructive system of hyper-consumerism can still be altered. Perhaps, what these individuals need is a walk in the woods. Not a weekend trip by private jet to an exclusive country club.

The Book of Zhuangzi suggests through numerous parables that when one is in nature the wandering mind has limitless creative potential. Florence Williams, the author of The Nature Fix, points to scientific studies that suggest that taking walks while listening to running water or birdsong in the forest for as little as 15 minutes can reduce cortisol levels, and more than 45 minutes can improve cognitive performance for most individuals. Some of us are rejuvenated by pink and purple sunsets. Others are drawn by shady brooks or a mossy ravine. Tranquility and healing can occur if each of us can discover a quiet spot where we can express gratitude toward everything that nourishes us: from the trees and sweet grass to the ubiquitous microbes within our bodies that defend us from disease. Through repeated walks and spacing out in nature, we can rediscover what makes us truly human. The benefits of “mind-wandering” can extend far beyond mere stress management to reenvisaging ourselves and our relationship with the world around us.

See also, from KJ 91: A Cabin In The Pines: On Urban Suffering And Chinese Landscape Painting, by Leath Tonino, and KJ95, our issue on Wellbeing.

Author

Jonathan Augustine

Author's Bio

Jonathan Augustine has spent most of his life in Asia since the 1970s where he is active in theatrical projects and volunteer activities. His academic and fictional works include Shadows of the Atomic Bomb『原爆の影』(2013), Karakuchi Onna『辛口女』(2010), Land of the Immortals『仙人之谷』(2005) and Buddhist Hagiography in Early Japan (2005).

Credits